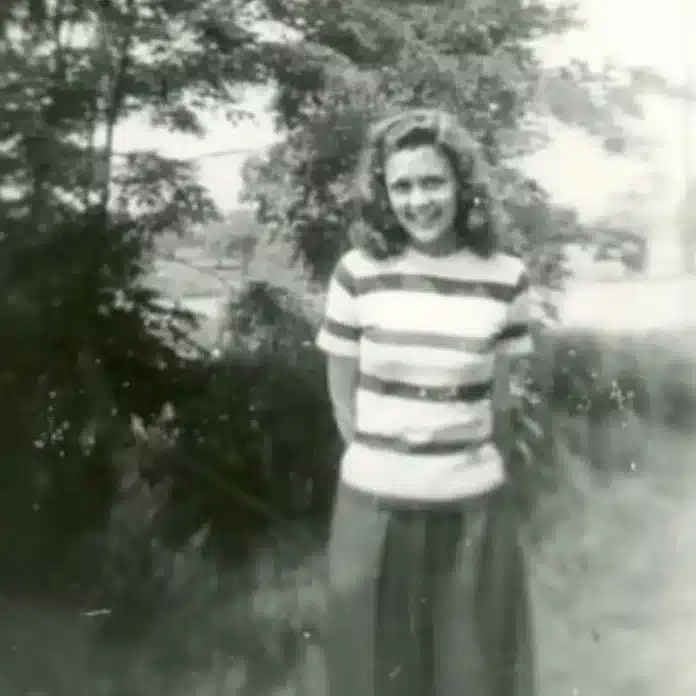

When my mother was alive, she never drove a car. She didn’t fly on airplanes, either or climb the slatted staircase to the observatory at the college where my father taught, to see the stars. My mom had severe anxiety and agoraphobia, and throughout my childhood, our one weekly family outing, besides attending church, was a trip to the public library.

But my mother drives now. She wears glamorous black sunglasses and a scarf around her neck as she roars off in her red Pontiac GTO, similar to the souped-up 8-cylinder Mustang I would have bought with my inheritance, if I’d been brave enough to rumble up in such a car to my job as a college professor in Los Angeles.

Recently, when I told my therapist about my mother’s post-death transformation, his face grew still, a noticeable effort to conceal his reaction. I don’t blame him. I’ve had a hard time believing it myself, but the truth is that my daughter Ivy is a medium, and according to her, my dead mother has things to say.

When grief-stricken people come to Ivy for a reading, she senses the personality and sees the faces of their departed loved ones clearly enough that she could draw their picture. The dead show Ivy images in her mind’s eye, and she describes these to her clients, evidence from their lives the dead can see, or items they remember: a teacup set painted with twin cherries, a toddler’s Jellycat sloth, a hidden box of love letters, lilacs that bloomed where a grapevine was planted.

I didn’t know Ivy was a medium until two years ago. She went to Dartmouth and USC, where she now teaches, and if anyone else had told me they could talk to dead people, I would have had the same reaction as my therapist. But Ivy has always been a thoughtful and serious person. After her fiancé, a beloved psychiatrist, drowned in a surfing accident, as she describes it, “the dead became too loud to ignore.”

Thanks to a research study that involved Ivy as a subject, I now understand that mediumistic experiences, whatever they are, often emerge alongside unexpected loss. When she first told me, though, I was skeptical. I teach critical thinking for a living. As a young mother, I’d left the evangelical church in which I was raised and had spent my adulthood as an atheist. To go back to believing there was an afterlife after all felt like reverting to an inside-out version of the organized religion I had years before dismissed.

But I wanted to support Ivy, somehow help her bear the weight of grief. To understand mediumship better, I set an appointment, using an untraceable fake identity, with Traci Bray, a medium certified by researchers affiliated with the University of Arizona. I had heard it suggested to ask a departed loved one ahead of time for a sign, and although I felt sure I would hear nothing of the sort, I asked to be shown the Christmas cookies with pastel-colored icing and sparkly sprinkles my mom baked with me and my sisters every year, a tradition I had carried on with my daughters.

“Hello?” Traci said on the phone. Her voice seemed surprisingly ordinary, and after offering to allow me to record our call, she immediately came up with the name of my high school boyfriend, the name of my youngest daughter, Allison, and an accurate description of our family dog, who had died years before. She also said my mom was there, showing herself, and gave my sister’s middle name as evidence.

My mom showed the specific grosgrain ribbons she’d tied on my braids in girlhood, then showed herself taking deep, relaxed breaths. Traci asked if that meant anything to me, and I thought back on my mom’s last days. She’d been intubated and I’d sat by her side watching the machine artificially, and what had seemed violently, pushing air in and out of her lungs.

My mom also showed herself reaching for a glass of orange juice from a refrigerator, and when Traci made a point of describing the glass as small, my eyes welled up. Many people drink orange juice for breakfast, but my family’s dietary habits were a defining feature of my childhood, which I have often recounted to friends. My mom grew up traumatized by an alcoholic father. She wanted to give me and my sisters lives of stability, and to her that meant a familiar routine. She made us the same breakfast every morning—one scrambled egg, one piece of toast, a large glass of milk and a small glass of orange juice.

Traci then asked if my mom had had Parkinson’s – no, I said, but she did have an essential tremor, which others often mistook for Parkinson’s. Was this coincidence? Just good guessing? Lots of older people have shaky hands. But of the many symptoms a person could have when they are aging, Traci had described the symptom my mom had found most distressing. In the last few moments of the call, Traci asked, “Did your mom have a special recipe for the holidays, some kind of sticky green spread or cream cheese you’d spread on crackers?” It took me a minute before it dawned on me. Was she seeing our Christmas cookies?

I found the conversation remarkable and moving, but later in the day I was surprised to hear Ivy had another message for me. “Gran’s here,” she said, and when Ivy described seeing a name-inscribed, silver chain link bracelet my boyfriend had given me in high school, my mind began to shift. I hadn’t thought of that bracelet for years. How would Ivy know something I’d forgotten about myself?

Still, trying to absorb the surreal possibility that my dead mother could talk to me felt difficult. When I was a small child, my mom sometimes disappeared into her bedroom for hours, leaving me to cope on my own. And although we had cozy times, too, Sunday night popcorn, reading in lawn chairs together in the front yard, and as many presents on Christmas and birthdays as she could manage, much of my young life revolved around her distress.

The year I was a sophomore in high school, my parents and sister and I went on a rare outing to a new restaurant at the mall, which was on the second floor, up a flight of red-carpeted slatted stairs. When we got there, my mom put one foot on the first step and one hand on the railing, but couldn’t get herself to go up. The restaurant was visible above us on an open balcony, and I remember gazing at the people chatting at tables, as my dad searched for the elevator. After we realized it was out of order, and we’d spent a few moments standing awkwardly around, we got back in the car and drove home.

When I was eighteen, my sister and I tried to teach her how to drive on a country road near our home in southern Idaho, but she gripped the steering wheel for only a few minutes before her arms began shaking from fright and exertion. I can imagine how she might have felt, the road stretching out into the distance, impossibly long, open fields all around. When she put on the brakes and the car jerked to a stop, my hand flew up against the dashboard, and she didn’t want to try again. Everyone drove in Idaho—it was the way we got around, and her refusal to take agency over that part of her life felt emblematic of the way fear was allowed to rule our lives.

But we didn’t press her on these issues. We kept silence around them; that was our family’s unspoken pact. And now in this moment, I was finding it hard to accept this new mom, talking to me so openly, as if my childhood trauma had never taken place.

I decided to schedule a follow-up call with Traci, to confide in her about Ivy’s mediumship experiences, and the conflict I was feeling. “They’re showing me your mother’s anxiety came partly from her own unrecognized psychic abilities,” Traci said, describing mediumship as a strange inheritance that often runs in families. Traci said her own family has refused to acknowledge her stigmatized profession and remarked that my open-minded curiosity was a gift to my grieving daughter, who was struggling with self-acceptance.

And whether I believed it or not, Ivy frequently felt my mom’s presence, so I kept listening. “Why does Gran keep showing me a single raspberry and then strawberry shortcake?” Ivy asked me one night.

I was stumped, then remembered the cereal heaped with raspberries I’d had for breakfast. That morning, I’d been thinking of my girlhood, and how fresh berries had been a rare treat. I have so much, I’d thought, feeling grateful. I had said nothing out loud to anyone about this, but through the images she was showing Ivy, my mom was bringing it up.

“We did have strawberry shortcake in the summer. I remember that now,” I said, laughing at my mom’s correction of my memory, a moment that felt like normal conversation between two people.

It took a while after I started hearing messages from my mom for me to say to her, “I know you loved me so much, but I wish you had been more consistently present for me.” It took guts to say that, even to a dead woman.

Through Ivy, she responded, “I’m so sorry. I will say I’m sorry as many times as you need me to.” And then she said, “that’s the reason why I’ve been showing up so consistently for you now, because I want to try to make up for that.”

Her words made me weep. There were regrets on my side, too. I’d felt guilty when she asked to live with me in Las Vegas where I had a teaching job at the time, choosing instead to visit her in Idaho at the assisted living facility where she spent her final months. But now she showed herself to Ivy in what was unmistakably her own sense of humor, flying over The Strip in a cartoon airplane, quipping, “Granny goes to Vegas! Can you imagine? That would have been a disaster!”

I’d also felt ashamed about the amount of my inheritance I’d wasted buying clothes online, but before I even asked, my mom communicated that shopping had been a form of self-care for a grieving daughter. She said she was glad I’d found a way to bring myself joy in a hard time. I hadn’t known how badly I needed to hear that, and a knot of tension released in my chest.

I marveled at all my mom seemed to know about the private moments of my ongoing life, and she responded by showing Ivy the “cone of silence,” the goofy device used on the TV show Get Smart to send secret messages, as if to show me I now have a direct pipeline to my mom with my thoughts. It seemed purely silly, another perfect example of her sense of humor, until I watched a clip of it again on YouTube, and listened to the dialogue in the scene. Max says, “Well, Chief, I appreciate you taking me into your confidence like this.” And the Chief replies, “Max, there is always someone in whom we must have faith.”

My other daughters say I seem lighter now, more attuned and present. I know intellectually from therapy that my wiring from my upbringing has the potential to tip me into fear and anxiety, but as my ongoing relationship with my mom has evolved, I can feel something inside me healing.

Recently, Ivy spoke as a medium on a podcast hosted by two therapists called Love, Sex, and Attachment about how evidential mediumship can help the grieving develop a more secure attachment through the cultivation of continuing bonds. Similar to narrative therapy, Ivy’s abilities have helped me rewrite my own story of loss.

Somewhere I read that healing doesn’t occur outside of relationships; healing occurs inside safe relationships. Perhaps the most convincing evidence that my mom really might be alive and well in another dimension: my relationship with her is finally becoming a safe place to be.

***

The ManifestStation is looking for readers, click for more information.

***

Your voice matters, now more than ever.

We believe that every individual is entitled to respect and dignity, regardless of their skin color, gender, or religion. Everyone deserves a fair and equal opportunity in life, especially in education and justice.

It is essential that you register to vote before your state’s deadline to make a difference. Voting is not only crucial for national elections but also for local ones. Local decisions shape our communities and affect our daily lives, from law enforcement to education. Don’t underestimate the importance of your local elections; know who your representatives are, research your candidates and make an informed decision.

Remember, every vote counts in creating a better and more equitable society.