In February 1998, I stood outside the home of a psychiatrist whom I had found in the Yellow Pages. I had made the appointment because I needed help with two important matters: to find out what was wrong with Dad, and how to fix him. I was 25 and had never sought this kind of help before. But my family was in a crisis.

The directions led me to an affluent residential area by the river in the middle of town. A sign by the front door instructed patients to walk to the back door and ring the doorbell. I hesitated for a moment. It wasn’t too late to change my mind. I could turn around, walk away, and forget the whole idea. I looked at the paver walkway. And when my legs started walking, they obediently followed the instructions, and at the back door, my finger pressed the button.

This obedience was a grin-and-bear-it skill I had learned in my childhood from observing Mom as she raised me and dealt with Dad. He was the only one in our family allowed to have a voice and to express his emotions. For decades, I thought this life skill had made me strong and independent, but in my late 40s, I learned that I suppressed my emotions, sometimes to the point of numbness.

I grew up in Sweden in the 1970s and 1980s. Mom worked full-time, and Dad stayed at home. Nobody ever cared about Mom’s occupation. But dads weren’t supposed to be at home. So, I suffered from worrying about the dreaded question: “What does your dad do?” And having to answer: “He’s unemployed.” I chose friends who wouldn’t ask me about him.

When some asked Dad what he did for a living, he would start talking about the vendetta against him. This all began when he and Mom attempted to start a produce farm and were denied bank loans to continue their business.

After it failed, Dad isolated himself in our apartment. He refused to visit with friends and relatives. He also refused to deal with the aftermath of their bankruptcy. Mom had to do it all. She hired a bankruptcy attorney and showed the debt collector around our apartment while he inspected our assets. She contacted a realtor to put our summer house property on the market and found a buyer for our Volvo station wagon. Per Swedish law, the debt collector couldn’t force my parents to sell our apartment. At least their entrepreneurial risk-taking did not make us homeless.

In an interview I watched, Kevin O’Leary, from “Shark Tank,” said something to the effect that all successful entrepreneurs experience failures. They grow from them and start over.

But there was no starting over for Dad. Instead, he spent lots of time in bed and blamed his enemies for conspiring against him and ruining his life. His mood was unpredictable and could quickly escalate into something scary and dangerous.

In our home, where I was supposed to feel safe and protected, Mom was powerless and unable to handle him. I would freeze up and imagine myself shrinking into an ant and running away. At the same time, I remained terrified and conflicted because my imagination couldn’t shrink Mom and rescue her from Dad or save Dad from himself.

At Dad’s lowest moments, often in the middle of the night, he kept us awake with his crying and threatening Mom with “doing away” with himself. One time, he almost succeeded. The police came, and he agreed to go to the hospital. I was seven.

While Dad was gone, we experienced a period of peace at home. For a few weeks, I could relax and focus on myself and have fun with my friends. I got a break from the war he fought, one where the real enemy was himself, and the victims, who suffered wounds and losses, were us, the ones who cared and loved him most.

Growing up, I kept everything that happened at home a secret. Raw and unprocessed, I stored it deep inside my body where nobody could see it or ask me about it. The war at home remained there for decades. I never talked about it. Nobody knew—until my appointment.

**

A petite older woman with a stern face opened the door to the psychiatrist’s house. She didn’t ask my name, only waved for me to enter and pointed to a couple of wooden armchairs.

“Take a seat,” she said and went to another room and shut the door.

I sat down and looked around. My eyes searched for something to latch onto, some kind of reassurance, a reason to stay, but they found nothing. The furniture, wallpaper, and pictures looked tired and dated. They belonged to a generation of adults who had turned their backs on me.

My inner voice yelled. This is a mistake. Again, I contemplated taking off. But just like earlier, my body obeyed, and I remained seated.

**

We sat across from each other in a pair of high-backed leather armchairs. I had anticipated a male version of the woman who had let me in, but instead, the doctor’s face was warm and friendly, and hairy, like a laid-back shaggy dog. My protesting inner self relaxed a little.

“What can I do for you?” He gazed at me with curious eyes. “You are quite a bit younger than most of my patients.”

“I’m not a patient,” I said. “I mean. I’m not here for me. I’m here to talk about my dad.”

His eyebrows went up. “This is a first,” he said. “I have never had anyone come to see me about someone else before. What’s the matter with your father?”

A hard lump formed in my throat. This was a first for me too. I had never shared my concerns about Dad with anyone outside my family before. I couldn’t speak right away, but then the words began to line up inside my mind, and I felt a sudden urge to let them out.

“Mom divorced Dad seven years ago. She moved out of the apartment where I lived growing up. Dad still lives there. But they never finished dividing up their things before he stopped opening the front door and cut off all contact. I haven’t seen him since before the divorce. He goes outside to visit only three places: the grocery store, the electronics store, and the post office. He buys empty cassette tapes and records messages on them. Then he mails them to people. He doesn’t write letters because nobody can read his handwriting. Sometimes I get two 60-minute tapes. He has pissed off his cousin with his tapes. Now the police are involved, and he has a restraining order against him. –But that’s not why I am here. The problem is that he’s unemployed. He refuses to answer the phone, sign any papers, or open the front door. And the apartment is in Mom’s name, so she has been paying all his bills up to this point. Years ago, she contacted the Social Assistance Office and showed them her divorce papers, because she couldn’t afford to pay for two apartments. They started reimbursing her for Dad’s costs. But now, after he turned 65, they won’t give her any more money because he qualifies for a social pension and needs to contact the Social Insurance Agency.” I took a deep breath and swallowed. The hard lump was still there.

The doctor had held his hands clasped in his lap while he listened, but now he cleared his throat and stroked his beard a few times before he spoke.

“Has your father ever been seen by a psychiatrist?”

I shared about my childhood and how Dad was hospitalized once in the early 1980s.

“I worked as a hospital psychiatrist back then,” he said. “I might have been one of your father’s doctors. The mental healthcare system has changed dramatically since those days. We used to be able to hospitalize people who needed our help for all kinds of reasons and keep them admitted for long periods, but not anymore. The laws have changed. Now, they must manage out there in society on their own.” His eyes met mine. “So, what does your life look like?”

I sat up straight.

“I’m fine.”

I shrugged.

“I go to school. I’m married…and pregnant.” The last part made me smile.

He tilted his head and smiled back. “You have a family.”

“Yes.”

He stroked his beard.

“But what about Dad?” I snapped—and immediately felt embarrassed.

“Your focus should be on your own family,” he said. “Don’t try to be a social worker and fix your parents’ problems.”

I slumped back into my chair while his statement swirled inside my head.

He continued, “There isn’t much we can do at this moment. According to the law, a person must be a danger to himself or others for the authorities to act. Currently, your father is neither. Besides his trouble with an angry cousin, he manages to live peacefully…in his own way.”

I tried to digest everything the doctor had told me, but it was too confusing.

“So there is nothing I can do?” I swallowed. The lump in my throat was becoming harder to control, but I refused to let myself fall apart. “Dad will never agree to meet with the Social Insurance lady to fill out the forms to start getting his checks.”

The doctor looked down at his watch. “We have to end our session here, my dear,” he said. “I have a patient sitting out there who can get rather difficult to handle if I let her wait too long.” He winked and smiled.

“OK, I understand.” I stood and offered him my hand to shake goodbye. I wanted to hurry up and leave.

“You know,” he said as he let go of my hand, “if your father doesn’t have any money to buy food, he can’t eat. Then technically, he is a danger to himself. You can contact his primary doctor. A nurse will have to do a wellness check. And then, it won’t be long before they must do something.”

There it was. The doctor had spelled it out. His solution sounded logical, even kind. But I didn’t know what an emergency commitment was. And if I had known then what would follow, I wouldn’t have had the courage to set the process in motion.

**

A month later, on a March evening, two policemen went into the apartment where Dad had just sat down at the kitchen table to have his supper, two fried eggs. The eggs were left untouched. The policemen didn’t wait for his cooperation. They grabbed him and said he was going to the hospital. With no winter jacket or shoes, they pushed him out the front door, down the stairs, and into the police car.

In a meeting with Dad’s hospital psychiatrist, I learned that Dad would need medication and help to manage his life to avoid a relapse into isolation. He asked if I would be Dad’s legal guardian. Right away, I knew that I couldn’t be that person. He wouldn’t listen to me. But what kind of person is a daughter who says no to helping her suffering dad?

The weight of responsibility rested like a sandbag on my chest and shoulders. Dad’s war and enemies weren’t real, but why did I feel like I had joined the vendetta that he believed conspired against him?

I remembered my own psychiatrist’s advice: “Your focus should be on your own family.” Then I understood. I couldn’t continue where Mamma left off. But logic didn’t help against the pain I felt in my heart as it tore apart when I said No.

A month earlier, I had felt hopeful. For the first time, I was old enough to do something. I was going to fix Dad’s problems and help Mom. But it turned out, I was still a naïve child. I didn’t foresee the consequences of my actions. Immediately after Dad was hospitalized, Mom cleaned out their apartment and contacted a realtor. I understood she couldn’t afford to pay for two apartments, but where would Dad live after he was discharged? Mom didn’t have a solution, but her answer was for an adult, not a little traumatized girl who wanted to rescue her parents. “I’m not his wife anymore,” she said. “He’s your problem now.”

What would happen to Dad? I loved him so much. Life was so unfair.

During my childhood, I believed I was smarter than Mom and Dad. As an adult, I would never make their mistakes. But look at me now. Instead of fixing Dad’s problems, I had made his situation worse.

I didn’t know what to do. I felt scared and alone. There was nobody in my corner, nobody who said: Wait a minute! Take a deep breath. You are brave. You do more than most people. Not until Ed showed up.

Ed was a short man with a tidy appearance and kind eyes. A retired insurance agent, he understood legal matters and the healthcare system. Up to this point, he had served as a power of attorney for a small group of individuals, but after meeting Dad, he agreed to sign up as his legal guardian.

Dad’s social worker introduced us in her office. In a previous meeting, I had told her that I wanted to be part of Dad’s support team. Concerned and suspicious of who the person was who decided to take legal ownership of Dad, I asked Ed why he decided to do it.

He smiled. “Your dad and I have a lot in common. We’re a similar age and grew up in the same neck of the woods. But to be honest, we just clicked.”

I believed him. Maybe it was his calm presence and confident voice, but his words wrapped around my tense body and squeezed me like a warm hug. I liked Ed from day one.

**

Dad passed away peacefully one night in March 2018. During those last 20years, thanks to medication and Ed, a guardian he grew to love and trust like a brother, Dad and I enjoyed a functional father-daughter relationship. But after his death, I learned there was a seven-year-old girl inside me who needed reparenting and healing—when I write, I can connect with her and explore and process our hurts.

Ann-Christine Vevera is a Swedish-American writer who lives with her husband, Matt, and two dogs, Breeze and Zuzu, in Ormond Beach, Florida. By day, she works as a physical therapist assistant in a busy hospital. And by night, and on her days off, she reads and writes memoirs, personal essays, and poetry.

***

Looking for your next book to read? Consider this…

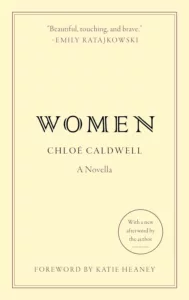

Women, the exhilarating novella by Chloe Caldwell, is being reissued just in time to become your steamy summer read. The Los Angeles Review of books calls Caldwell “One of the most endearing and exciting writers of a generation.” Cheryl Strayed says ‘Her prose has a reckless beauty that feels to me like magic.” With a new afterward by the author, this reissue is one not to be missed.

***

Our friends at Corporeal Writing continue to offer some of the best programming for writers, thinkers, humans. This summer they are offering Midsummer Nights Film Club: What Movies Teach Us About Narrative. Great films and a sliding scale to allow everyone the opportunity to participate. The conversation will be stellar! Tell them we sent you!

A brave essay!