By David Simmons

We ran so fast I almost lost my schizophrenia papers. I hadn’t slept in days so my shoes were soggy and the footfalls sounded like wet sacks of chili hitting the sidewalk.

Chauncey yells out behind me, “Hold up bruh, you dropped your schizophrenia papers!”

I keep running, my sneakers splattering across the block. I bend the corner at 15th and Center Street, keep going, Chauncey catching up to me.

Americans are stupid. They’re stupid because sixty-four percent of Americans think schizophrenics have split personalities. I don’t have split personalities. I barely have one personality, but then again, I don’t actually have schizophrenia.

I just have the papers for it. They give them to you when you have nowhere to go.

Sometimes you can’t go straight home from prison, especially if you don’t have a home. If you can’t provide an address, they make you check in with the Department of Behavioral Health in that big, menacing, dystopian-future building on E Street. There’s this guy who works there, Tayvon Lancaster, Lannister, something like that. The guy’s got this big, swollen belly that sits like a bowling ball beneath his bird chest. Guy wears his slacks with the front pleats over his distended stomach, stuffs the bloated thing underneath the waistline of his pants. Then he gets one of those braided belts, like the kind Salvadorian children wear to church, and he wraps it around the whole mess. The whole get up makes him look like a tall humpty dumpty.

So this guy—Tayvon Lancaster, Lannister, something like that—is the one who does your orientation. He says community college criminology degree buzz words like “reintroduction” and “reintegration ” and how “it can be difficult for one to adapt to living with others after being institutionalized.” At this point you feel like if anybody is familiar with the social etiquette that is required for living with others, it would be you, so you tune the bastard out and eye-fuck his tumescent belly.

Tayvon Lancaster, Lannister, something like that; he takes you to the psych doc because you have to see the shrink before they can discharge you. The doctor looks like broccoli. She’s tall and shapeless, like two parallel lines drawn up into a grey poof of short, curly hair. Exactly like broccoli. She makes you do serial sevens, where you gotta count backwards from one hundred by seven.

She asks you what your ideal circumstances post-release are.

She wants to know if you have a poor sense of smell.

It’s difficult to answer the last question because how do you know if you have a poor sense of smell comparatively to anybody else? You can’t smell what they smell. And I can’t think of anything to tell her in response to the other question so I’m all, “I’d really just like a decent meal and a shower by myself.”

The doctor says, “What is your history of psychiatric hospitalizations? Have you ever been certified for treatment?”

“Yes,” I tell her.

“Do you hear things other people don’t hear or see things other people don’t see?”

“How could I know what other people don’t hear or don’t see? If I told you that I could you would say I was crazy for claiming to be a psychic. It’s lose-lose for me.”

The broccoli-looking doctor scribbles something down in her notepad.

“You wanna hear something that’s actually crazy?” I ask her.

She stops scribbling and looks up from the notepad.

“I totaled my first car three months after buying it with money I had saved up from working at Blockbuster and selling drugs,” I tell her. “It was a 1995 Lincoln Mark VIII. Midnight blue with the air suspension compressor. If that air ride shit ever broke, the repair bill would cost you more than the car was worth. After I crawled out of the sunroof of the vehicle, I looked up at the walls of the ditch I had crashed into. One by one, what must have been the lights in the windows of houses went on, surrounding me in yellow rectangles of light. One by one, a firetruck, an ambulance and a cop car pulled into what I soon discovered was a cul de sac in a residential neighborhood, meaning I had crashed my Lincoln into a ditch at the end of a cul de sac.”

“How did that make you feel?” the doctor asks.

“It was all very surreal. One minute I was on the highway and the next I was in a ditch or ravine or something. When the cop gets out of his car, the first he does is ask me if I like ice cream. He says to me, ‘Do you really like ice cream or something?’ He doesn’t even ask me for my license or registration. He just wants to know if I like ice cream. And I’m all like, ‘What does that even mean? Doesn’t everybody like ice cream?’ So then he’s like, ‘I just figured you really liked ice cream, you know, on account of your car and all.’ And I’m eighteen years old and disoriented from the crash and confused because this cop is asking me if I like ice cream. Why would he do that?”

“I don’t know why he would do that,” the doctor says. “Why do you think he would do that?”

“Well that’s just it, “ I say, raising my voice a little, “That’s what I’m trying to tell you. I don’t know why he would do that. And what was it about the car I was driving that insinuated I liked ice cream? Was it the color?”

“Let’s move on. Do you feel that—”

I cut the doctor off. “Was it because I crashed the car into a ditch? I was barely an adult. I had just learned how to drive. And how does that relate to ice cream? It’s all I think about.”

“That was a very long time ago.”

“Time doesn’t change anything,” I tell her, sinking my body into the couch and crossing my arms. “Everything is inevitable. One day your parents picked you up, put you down, and never picked you up again.”

The doctor is writing something down on her yellow legal pad. I can see that she’s got a list of words in a vertical column going down the left side of the page. I can’t read the words but it looks like she’s putting some kind of symbols or marks to the right of the words. I decide to stop talking.

“If you see things people don’t see,” the broccoli doctor says, “are they in the periphery of your vision or in the center?”

I move my eyes from side to side and the top of my skull is electrified by a serotonin brain zap.

The doctor continues to vomit stock questions at me. “Do you see these things in daylight? Or only in the shadows?”

I tell her that everything I see is in the shadows and how the first time I smoked PCP with Chauncey I watched him cough up a piece of flesh. It was a slug-shaped thing, something pink and made of meat. She asks me if I’m thinking about hurting myself or others. I tell her how I picked up the slimy thing that Chauncey coughed up onto the street and put it in the fifth pocket of my jeans and saved it, in case it turned out he needed it. She asks me if I need any medication. I tell her how the skin of my hands are just gloves for my true hands. She writes me out prescriptions for Serequel, Risperdal, Lexapro, Zyprexa and some green papers with information about me that translates into a billable diagnosis or two for her.

And that’s how we ended up where we are now; Chauncey and I, running down Shattuck Avenue because we just robbed the Cheeseboard Collective; my schizophrenia papers flying out of the front pocket of my soggy hooded sweatshirt.

Schizophrenia papers. They give them to you with your medications. That way, if you get stopped somewhere by the police they don’t have as many questions for you. The papers explain it all. The papers are green and folded in half, then folded in half once more. The police still ask you plenty of questions, but not quite as many as they would if you were sans schizophrenia papers.

When the papers fly out of the front pocket of my hoody, they unfold, flapping in the wind like the wings of chartreuse birds. I spread my own wings and manifest thusly; spreading my blackened feathers across the sky as I take flight and disappear into the sinking California sun.

David Simmons spent his childhood within the juvenile justice system in various institutions and holding facilities. His work has been praised by D. Harlan Wilson, Brian Evenson and Snoop Dogg. He has been featured in the Washington Post, Prometheus Dreaming, 3 Moon Magazine, Across The Margin and the Washington City Paper. David lives in Baltimore with his wife and dog, where he is responsible for creating the colloquialism “Whole Time.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

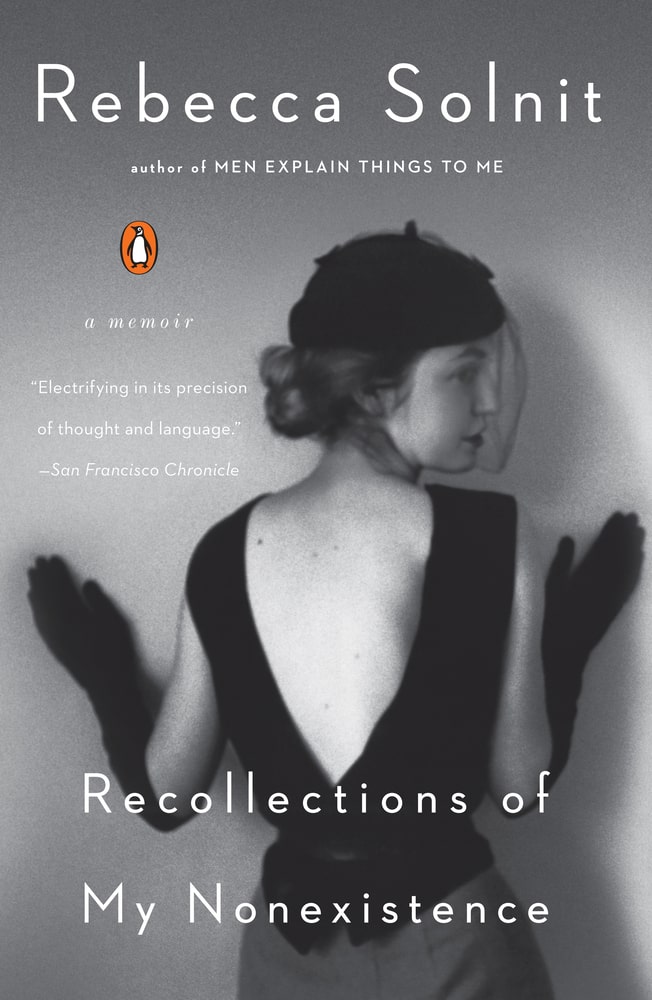

Rebecca Solnit’s story of life in San Francisco in the 1980s is as much memoir as it is social commentary. Becoming an activist and a writer in a society that prefers women be silent is a central theme. If you are unfamiliar with Solnit’s work, this is a good entry point. If you are familiar with her writing, this is a must read as she discusses what liberated her as a writer when she was discovering herself as a person.

Pick up a copy at Bookshop.org or Amazon.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Anti-racist resources, because silence is not an option

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~