By Abby Schwartz

I’m scrolling through Instagram while eating my oatmeal. It’s August 2019 and writer Cheryl Strayed has posted this announcement: I’ll be teaching a workshop at the @kripalucenter in April called The Story You Have To Tell. It’s for writers at all levels of experience—really it’s for anyone who wants to crack it open to get at the good stuff inside…All you need to bring is a notebook and pen. I hope to see you there!

I’m frozen mid-spoonful, her words an electric jolt to my heart. I recognize this as a moment to seize without overthinking.

I respond to the post: @cherylstrayed your words always inspire me to be brave and authentic so I am going to push aside my fear of going this alone and sign up. Thank you!

I am thrilled when, moments later, Cheryl likes my comment and responds: @abbys480 You’ll make friends!

I’ve been a professional copywriter for 20 years, though I started in advertising as an art director. Back then, we worked in teams—an art director paired with a writer—or with the entire creative department in one room, scribbling ideas with black Sharpies and tacking them to the wall. Brainstorming was energizing; we fed off one another. When our sessions got long we grew punchy, our ideas verging on the absurd. You could hear our roars of laughter down the hall.

What I miss about those days is the camaraderie. Though our group was competitive—each determined to be first with the winning idea—we supported one another, celebrated our wins and created a safe space where no idea was off limits.

Even as an art director, I approached each concept through words, crafting a headline before giving thought to the visuals. My creative director Tom was one of the original Mad Men, a copywriter who worked at some of the biggest Madison Avenue firms in the sixties before starting his own Philadelphia agency. He pulled me aside one day and told me I was a good writer, that he could see me writing a book one day. His validation lit something in me. I tucked his words inside—a glowing coal that kept me warm.

At my therapist’s I tell Dr. G. about registering for Cheryl Strayed’s writing workshop. She can see how excited I am and thinks this is a wonderful idea. She tells me, “You are someone who is open to trying new things and is enthusiastic about them.”

I like viewing myself through this lens. I’ve only recently begun the work of unpacking the fear and anxiety I’ve stuffed deep down to avoid facing those feelings head-on. I sought therapy because trauma will find its way to the surface; in my case I was spiraling emotionally, grasping at any semblance of control over my daughter’s life now that she was a young adult, her health no longer mine to manage.

Since being blindsided by her diagnosis of cystic fibrosis 20 years earlier, I’ve lived in a state of hypervigilance—on high alert for the next lung infection, medical complication, hospital admission and worse.

In my early days of therapy, we talked about my childhood. The third youngest, I watched my older brother and sister fight with our mother, whose short fuse could detonate at any moment. I navigated those years with my ears finely tuned to detect a tone of voice, a slammed door, a heavier footstep—clues that my mom’s mood had taken a turn. I learned to keep a low profile and stay off her radar. I remember hovering silently outside my parents’ bedroom late one night, having just thrown up in my bed. I needed help but was scared to wake my mom. I stood in their doorway, willing my dad to notice me first. Afraid to use my voice.

In therapy, I discovered that the hypervigilance I had assumed was born of my daughter’s illness had roots that ran deeper. My state of high alert was my mode of self-protection growing up. But here’s the thing about being on high alert: when your guard is constantly up, it’s like living behind a wall. It’s hard to connect to others from behind a wall.

I rely on written words to create order in my life. On paper, my thoughts line up obediently, no longer tumbling inside my head like clothes in a dryer.

In my early thirties, when my daughter was diagnosed, writing was how I grabbed the reins to keep us from hurtling off a cliff. I wrote heartfelt letters to raise money for CF research and crafted emails that explained the disease to her teachers. I began documenting each doctor’s appointment, lab result and breathing test in a notebook. I created lists and charted her therapies. My child needed more than a dozen prescription drugs a day to keep her alive. Writing kept me vigilant and prevented details from slipping through the cracks.

Soon after, I left my corporate advertising job to start a freelance healthcare marketing business, and I added copywriting to my creative services. My crash course in managing a chronic illness had given me an insider’s perspective on the patient experience and I recognized that there was value in what I had to say.

There is power in naming things and using words to define yourself. I had been secretly keeping that warm coal of encouragement from my creative director glowing for years, but it was only after I spoke the words out loud, I am a writer, that I stepped more fully into that identity. Still, I remained one step removed from telling my own story.

Though I write professionally, I’m not writing as myself. I am a surgeon explaining breast reconstructive techniques after mastectomy. I am a patient describing his recovery from stroke. I am a hospital president congratulating her staff for earning national recognition.

Many years ago, I was contacted by Roland M, a bestselling writer who was working on an article for the Philadelphia Inquirer about cystic fibrosis. Mine was one of several families he profiled. Roland’s daughter had also been recently diagnosed, and we became long-distance friends, keeping in touch by email.

A few years later, he wrote a novel about a young woman with cystic fibrosis. As part of his research, he stayed with my family overnight—our first in-person meeting—and came along to a pulmonology checkup. He asked if I’d be willing to share notes about my experience and I remember the thrill of the invitation—permission to tell my story.

I wrote pages and pages, the words flowing like water. When I lived it I couldn’t write about it, but now it was all pouring out. After all, this was only for research—I was simply providing background for the real writer. What I secretly wished was this: that Roland would share my writing with his agent, who would call and offer me a book deal. You have a story to tell, he would say. The world needs to hear it.

In my early forties, I responded to a call for writers and became a regular guest blogger for a website about hooping. The hula kind. Blogging for Hooping.org was a way to scratch my creative writing itch. I had been bitten by the hooping bug and in a fog of euphoria, I enrolled in Hoop Camp, a three-day gathering of hula hoopers held annually in the redwoods of Northern California. A Hoop Camp virgin, I would document my experience for the blog. I brought my sister Sue along for company and a shot of courage.

On our first day, I looked around and regretted my decision. I didn’t fit in with these younger women and men with their toned and tattooed bodies, multiple piercings and outlandish costumes. Yes, I could keep a hoop spinning, but these people were Cirque du Soleil-good—light years more advanced in their hoop-dance skills. I felt myself shrinking self-consciously.

That evening, I introduced myself to a group of women and something shifted. They recognized my name and told me they were fans of my writing—that my posts were relatable and authentic. I beamed. For the rest of Hoop Camp, I felt like I belonged. I participated in workshops by day and uploaded a new column each night. Sharing my experiences through the eyes of a journalist lent legitimacy to my presence. Writing granted me permission to try, fail, and look foolish. Nora Ephron famously stated, “Everything is copy.” Today’s embarrassing gaffe would be recast as tomorrow’s humorous story.

I am hoping to find similar inspiration from Cheryl Strayed’s workshop at Kripalu. Perhaps my experience navigating the trauma of a child’s life-threating illness could be transformed through writing into a story of hope. In her book, Braving the Wilderness, Brené Brown writes about the power of art. In this excerpt she is speaking about music, but it applies equally to writing:

“Art has the power to render sorrow beautiful, make loneliness a shared experience, and transform despair into hope…Music, like all art, gives pain and our most wrenching emotions voice, language, and form, so it can be recognized and shared. The magic of the high lonesome sound is the magic of all art: the ability to both capture our pain and deliver us from it at the same time…The transformative power of art is in this sharing…It’s the sharing of art that whispers, ‘You’re not alone.’”

Cheryl Strayed’s book, Wild, is what first put her on my radar, but it’s Tiny Beautiful Things, her collection of advice columns, that I turn to repeatedly for solace. Her voice is a whisper in my ear letting me know that even when life is brutal, I am not alone.

I’ve been obsessed with reading my entire life. Books have been my doorway to escape, enlightenment and connection to the human experience. As a little girl I read under my covers, a flashlight clutched in one hand, on high alert for footsteps on the stairs, terrified of being caught by my mother awake past my bedtime.

Reading transported me to distant places, parallel universes containing other lives I might have lived. In sixth grade, when I discovered Judy Blume, the telescope flipped and I was the one who felt seen. I’d never before read an author who spoke to me in such a real and personal way. Judy had a way of validating the awkwardness of adolescence and normalizing the things we’ve all felt and done but didn’t dare speak of out loud.

As a teenager, books allowed me to connect with my mother. An avid reader, she’d take me to our local library where we’d collect our haul for the week. She’d hand me books that she loved, further expanding my world. When I toyed with the idea of being a veterinarian, she introduced me to James Herriot’s series about his life as a country vet in England. She put a copy of The Thorn Birds in my hand during my freshman year of high school and I swooned over the epic, forbidden love story. We passed Sydney Sheldon thrillers back and forth and shared trashy novels by Jackie Collins and Judith Krantz.

Even at my lowest, when my daughter was hospitalized, books provided a lifeline. I’d lie awake in the dark on the stiff vinyl daybed, reading by flip-light as the night nurse drifted in and out of our room to check vitals and reset the beeping IV pump. I seized on memoirs, looking for proof that humans were resilient. If that writer could survive her own trauma to reflect on it today, maybe I could get through the uncertainty of these days and tell my own story in the future.

Cheryl’s workshop, The Story You Have To Tell, will be my way in—the tool I use to drill past the protective barriers I erected in my mind; the walls preventing me from writing about the most defining moments of my life. Through memoir, I want to process my experiences in order to transform them. To reframe the narrative in a way that allows me to see myself not only as the timid child and the anxious mother, but as the strong and resilient woman who found beauty amidst the pain. And just like the writers who made me feel seen, I want to be that person beaming out signals in the night. Reaching the person who lies awake in the dark, seeking solace by flashlight.

My weekend at Kripalu is six weeks away. I wonder how many people will be there? I call the venue and ask. Over 200. This is a disappointing development.

In my fantasy, our group is small, maybe 30 max. I read my work out loud and Cheryl praises it. She pulls me aside after class to tell me I have real talent. We hit it off over dinner, bonding over conversations about her late mom and my late dad. We talk about books and dogs and kids. We stay in touch. She becomes my writing mentor and recommends my new memoir to her followers, catapulting it to the top of The New York Times bestseller list. She introduces me to her writer friends—modern-day Judy Blumes whose words are a balm to my soul: Liz Gilbert, Pam Houston, Glennon Doyle. They welcome me to their circle. Reese Witherspoon chooses my memoir for her book club, as does Oprah (as long as I’m fantasizing).

Cheryl’s workshop will be page one of a new chapter in my life. The spark of permission granted by my former creative director has fanned into a roaring flame. Now that the workshop is 200 people, my writing had better be damn good to stand out.

It’s now late March 2020. Cystic fibrosis is primarily a lung condition and this novel coronavirus poses a direct threat to my daughter’s life. Cheryl Strayed’s workshop has been a beacon calling to me for the better part of a year, but that no longer matters. Kripalu is a yoga center built on communal gatherings. To expose myself to large numbers of people from all over the world is to put my child at risk. According to the cancellation policy, I have a two-week window in which to cancel and get a refund. I make the decision to pull the plug. Two days later, Kripalu cancels the retreat and shuts its doors for the foreseeable future.

To say I’m disappointed is an understatement. I had psyched myself up to push beyond my fears, befriend a group of strangers, and—inspired by Brené Brown’s Daring Greatly—embrace vulnerability by exposing my insides through writing. It’s now up to me to keep that flame alive.

Today is the day I would have driven to Kripalu. These weeks of quarantine have been stressful, pushing my brain into fight-or-flight response. Still, I recognize that we are in the middle of something historic and I decide to start journaling again as a way of processing my emotions and capturing these extraordinary moments in real-time.

I pull a Moleskine notebook off my shelf but before I write, I reach for my phone and scroll to Facebook. I’m not sure what compels me to check my newsfeed at this moment. I see a post about a project called The Isolation Journals. I click to the page and read the description: A global movement cultivating community and creativity during hard times.

TIJ is a 30-day project conceived by Suleika Jaouad, a writer and memoirist who wrote her way through cancer in her twenties. For the month of April Suleika is offering a daily writing prompt, with help from a talented pool of writers, artists and musicians. The prompts can be used for journaling on our own or we may share our writing on the private Facebook page.

I begin reading people’s posts. I write an essay and upload it. Within minutes it receives a handful of likes and positive comments. Fueled, I start writing daily and interacting with others, offering feedback and support.

We begin to know each other. We remark on the safety we feel sharing intimate thoughts in this private space. Day by day, more people join. This space feels sacred. There are no trolls, political rants or snarky memes. There are raw, painful posts about grief and shame and loss. There are beautiful essays about love and life and what it feels like to blindly feel our way through the long days of quarantine. There are hilarious parodies, song lyrics and experimental poems—the talent on these pages shines brightly. We are tender with one another. We encourage and celebrate each revelation and, word by word, we build a community. I imagine Cheryl Strayed whispering encouragement in my ear. @abbys480 You’ll make friends!

By popular demand Suleika expands The Isolation Journals from 30 days to 100. My writing muscles are not only warmed up, they grow stronger each day of this project. I write about growing up with a tough mom. I post tributes to my loving dad and share what it was like to lose him to cancer. I open up about my daughter’s illness and my fear of her dying young.

As a little girl, my mother would say to me, “Will you just be quiet? Stop talking so much.” She taught me that to speak is to invite criticism and conflict.

I am no longer that child who needs permission to speak. I have learned the power of words as a tool for transformation and connection. With every prompt I am strengthening my voice and taking a sledgehammer to those interior walls. I am, in Cheryl’s words, Telling The Story I Have To Tell to a global community more than 7,000 strong.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

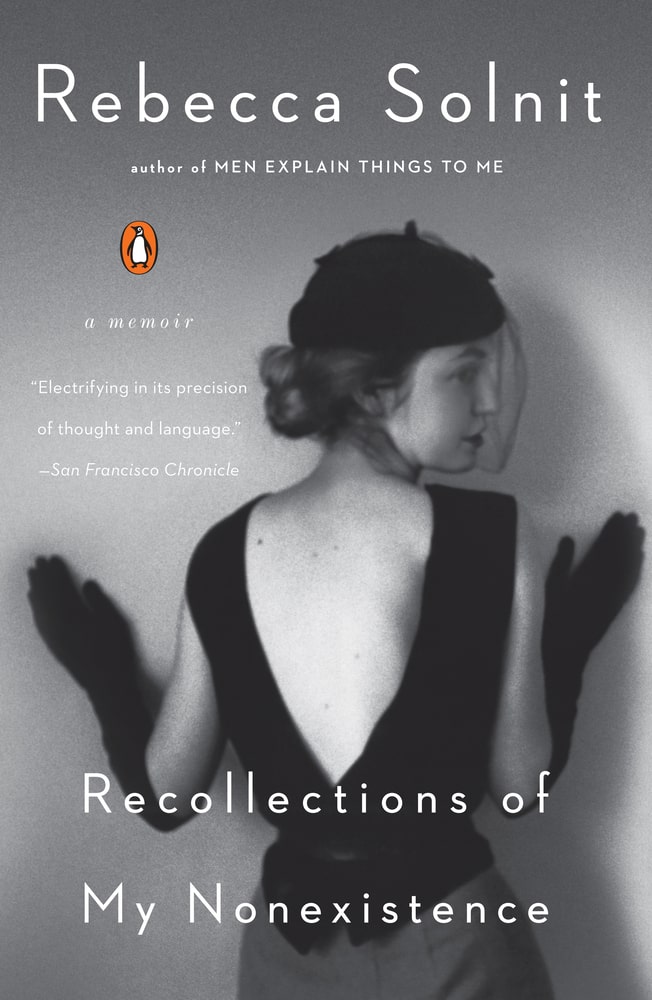

Rebecca Solnit’s story of life in San Francisco in the 1980s is as much memoir as it is social commentary. Becoming an activist and a writer in a society that prefers women be silent is a central theme. If you are unfamiliar with Solnit’s work, this is a good entry point. If you are familiar with her writing, this is a must read as she discusses what liberated her as a writer when she was discovering herself as a person.

Pick up a copy at Bookshop.org or Amazon.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Anti-racist resources, because silence is not an option

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

beautiful piece, abby. i’m so glad you’re writing. and writing and writing.

You got this, Abby! You’ve primed the pump and now your words flow freely. May you never turn off the faucet.

Beautiful essay Abby. Proud of my cousin— not surprised of your talent as we’re lucky to have alot of it in our families!!