By Laura Cline

I feel her following me. The ghost.

Somehow, it is already seven p.m. My hands are under the hot running water, rinsing the dishes and leaning over to put them in the dishwasher. The little girl voices swirl around me. “Girls, time to settle down.” They don’t hear me. I keep rinsing the dishes and the ghost wraps her arms around mine- strangling- embracing.

I’ve been here before. This feels familiar.

Not that I have lived through a global pandemic, but my heart has been in this place, my head, my hands, all the parts of my body. My days have melted together into the longest day, the mornings weeks, months from the nights. The rhythm of my day is need- food, water, attention, sleep.

I wake up every morning and immediately feel the fog pull me back under. I haven’t slept enough the night before. I was up late folding the laundry, slipping into the warm water of the bath, rocking the baby, holding her to my breast. I hear the voices, the cries. “Mooooooom, mommy, get me mommy.” This day will be just like the last. I put on my glasses so I can see and pull back the covers. The ghost sits in the rocker across the room. My eyelids feel heavy, made of lead.

The television is always on in the background, but I barely hear it. My daughter asks questions about what is happening. “What is she doing, mommy?” “I don’t know, honey. I wasn’t paying attention.” Instead I scroll though post after post on Facebook. I stop when I see one about the virus, when I see one about the baby. I read it and feel it sewing the sides of my rib cage together, the tightening of uncertainty. When will it be over? Will this last forever?

After my daughter was born, I was diagnosed with PPD, PPPTSD, PPA, and PPOCD. Four acronyms, but one feeling. One ghost, drifting through her days. One shadow, drawn in tears.

COVID-19 is it’s own ghost, invisible, but we all know it is there.

The afternoons are the hardest. I’m at my worst. Most days I feel like I am giving my ghost a piggy back ride, dragging her around the house by her ankles, asking her again and again to please leave me, but she doesn’t listen. Most days, I curl around my daughter for a nap in my king sized bed. I leave the window open and a warm breeze blows the blinds and taps them against the window. I feel the softness of my daughter’s blond hair pressed against my lips. Sometimes I sleep and she doesn’t. She wakes me up, and my heart pounds, I feel dizzy. Where am I? What day is today?

After nap, I feel like I’m just waiting to sleep again. Am I awake? I feel raw on all my edges. My nerves jitter around in my body. So many sounds: squeaks and screams and crashes. My daughters’ sticky hands and sticky faces grab my hands and my clothes, wrap around my neck. They run wild, play aggressively, fall and cry, and fall and cry. They are all scraped knees and off the wall ideas. I look out the window again and again. Is my mom’s car in her driveway? Should we get in the car and drive somewhere? I crave talking to another adult. Out in our shared yard, my mom and I talk about the news of the day, what will happen next, what did the girls do today, as we pick up weeds from the driveway, water the plants, sit six feet apart in chairs. My youngest always runs right up to her grandma, “No, June. Space. The virus.” They have seen her, hugged her, kissed her goodnight almost every day of their short lives. When we go inside, some nights I break. I scream at the top of my lungs in the middle of the kitchen. I sob until I can’t breathe. I kick around the toys on the floor, the trash, the crumbs sticking to the bottoms of my feet. Some nights I am even, Zen almost. Numb. We laugh at the dinner table, play Bob Marley and Elton John, have dance parties, read books, snuggle and eat chocolate. When I look in the mirror, my face is the ghost’s.

Every night it seems we go to bed later. The sun lingers. It is almost summer. It is mid summer. It is the heat of the longest of summers. Some of the voices on the news wonder if the heat will kill the virus, render it dormant, but it doesn’t hibernate. It still lurks in our breath, on our fingertips.

My firstborn came in the summer. One afternoon in July, I swaddled her up and put her into her rocker. She fell asleep and I waited for her to jerk awake, like she always did. Instead, she stayed quiet, and outside it began to rain, one of the early Monsoon storms that season. I turned on Fleetwood Mac. I was still. I felt like I was flying.

One day while I am watering the bush in front of the house, a bird shoots out. My mom tells me that she has seen the bird too. “It must have a nest there.” The next day, the kids and I trim back the bush. “Don’t touch the clippers. Pick up the leaves.” Eventually, we can see the nest near the edge of the bush, four tiny eggs inside. “Don’t touch them,” I tell the girls, but later that afternoon, I find them in the front, hiding their hands behind their backs, a cracked piece of shell on the ground. “I saw the tiny beak, mom,” my daughter tells me. My heart cracks and fissures like the shell. I hope that the mama will come back. I tell my girl that the bird is dead; that cracking it’s shell killed the bird. Her sister tells everyone, “The bird is dead, dead, dead. Gracie killed the baby bird.” “Stop it,” she shrieks, “they already know.”

The next day I go out and rustle the leaves on the bush. The mother bird flies out and hops across the yard. She came back.

Every morning my girls want to check on the eggs. I feel like I am holding my breath. I so badly don’t want them to be disappointed. How much loss can any of us stand?

The ghost has felt the hot summer sun on her shoulders and the back of her neck. She has felt the sting of the sweat running into her eyes. She watches like the mother bird, shooting out, anxious, to watch as giants hover over her babies, with their careless hands. Those hands already took one of them. Will they take the others?

But they don’t. The eggs hatch and the babies – two of them- are there in the nest, naked, tiny, eyes glued shut, organs and veins just visible under their translucent skin. They grow patches of feathers. My daughters give them names: Tiny and Flower. One day, one of them is gone, just a rustle in the bush. I push the girls on the swing, my feet in the warm sand, and when we come back, both baby birds are gone. Did a crow eat them? A javelina? Did something invisible take them away?

There are orioles all over the yard. Some days, we think we see the babies, slightly smaller than the others, eating at one of our feeders. The girls stand at the window, yelling, “I see them! Tiny and Flower!” I see them too, I think, and I almost believe it. “I see them, too.” My ghost nods.

We leave the house just a little for a few warm weeks at the start of summer. We go to the playground. We play with friends. The kids are almost like kids again. I start taking the baby places. She is stronger, bigger. They are the healthiest they have ever been. While we are out, I feel alive. When I come home to the house, I feel the energy drain out of my body. The house is a succubus. The ghost is always inside.

And the virus descends. Overnight, eleven people die. I don’t know them, but I feel their loss. Were they alone? I know they were.

I can’t control it anymore. The chaos descends. Every day is a whirlwind, and I want to get back in bed as soon as I get out of it. The laundry piles up, the floors are dirty, every thing is wet. The clutter makes me crazy. I throw things out with abandon. We take out the trash again and again. I rage. I cry. I laugh at my kids’ antics. They start to talk like me, to become me. I wait for night when they go to sleep. When I can breathe. The sun stays out and they go to bed later and later. Will it end?

When I find out the kids will be going back to school, I am terrified and exhilarated at once. This must be how the mother bird feels when her babies leave the nest? The act of protecting them, of holding them under my soft belly, is exhausting. But outside, there lurks the invisible danger of the virus, of the unknown, of the dark chasm of what the future will hold for them, for all of us.

The ghost sits down next to me on the couch, surrounded by the mess of the day. She takes my hand. We wait together.

Laura Cline is an English teacher at a community college with an MA in Literature from the University of Arizona. She has published both fiction and non-fiction, including an article about birds and babies at Motherwell, and an essay titled ‘Dear Left Big Toe‘ published in Entropy.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

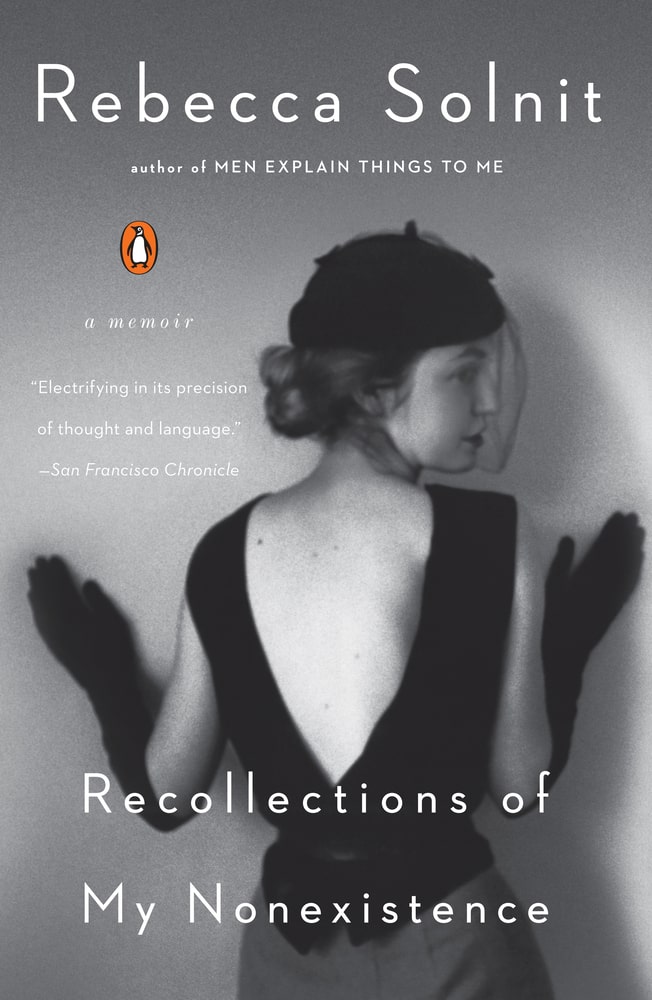

Rebecca Solnit’s story of life in San Francisco in the 1980s is as much memoir as it is social commentary. Becoming an activist and a writer in a society that prefers women be silent is a central theme. If you are unfamiliar with Solnit’s work, this is a good entry point. If you are familiar with her writing, this is a must read as she discusses what liberated her as a writer when she was discovering herself as a person.

Pick up a copy at Bookshop.org or Amazon.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Anti-racist resources, because silence is not an option

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~