by Bruce Crown

Everything had been hollowed out, especially the people, when I checked in. All sunny resorts are inherently the same. A consortium of young and old people sleeping in vomit, talking through cigar smoke, and swimming in low-range rum. I noticed it as soon as I entered. The Cuban peso was as strong as the American dollar. This amused me greatly. Not because Cuban money is worth more or less; I have no opinion on that. What amused me was that every time I needed money changed, the mob of tourists both in front and behind me would complain about this fact. They knew that their money was worth more, and they wanted to spend it here, to help Cuba by buying things to bring back home.

On the first day, the sun blazed as if to burn the darkness out of me, the abyss that had become a threading existence of booze and despair. The smoke trail of my Cohiba rose and misted towards that yellow star in the middle of the clear blue sky. I sipped what was left of my pineapple juice unable to quench the chasing shadows of my thirst. Just another drunk whose money can buy more booze here than back home.

“It’s too hot,” I puffed smoke to no one in particular.

“Yeah… the weather’s nicer in Havana. I’m from Trinidad myself but this sun feels… different. Hey! Where you goin’?”

“Thanks,” I turned back towards the bald and austere man who had a body that glistened with muscles under the infinitely clear sky.

Why, I thought later, did I immediately get up and accept the idea that the weather would be nicer in Havana than in Varadero? The place where I’d spent the last fortnight drinking and watching the waves wash more and more of the sand away hoping that one day it would wash it all away.

“Motorcycle,” I pointed around where the bikes sat around the lobby. “Havana. To rent.” I needed the cool breeze in my hair.

“Sir, have you been drinking?” it was a different concierge than usual. This one had green eyes and spoke perfect English.

I couldn’t help but wonder, whether from her perceptive, the transitive beings that come from ‘mainland nations’ are simply objects that move between shaded patches of sand while the background rattling of empty bottles ensures that they are all the same despite their faces and the flags on their backpacks changing every few days.

“It’s 10 A.M. amigo. Who drinks this early?” I slid my American Express card across the counter. “Give me something fast. 600CCs or more,” smiling like a sucker because I hadn’t been sober since I left Toronto and even then it was a toss-up.

“We don’t rent motorcycles here. You can rent a scooter if you like. But you can’t go to Havana with it.”

“A car then?” my disappointed grimace was hard to contain.

“That could work. We have a Volkswagen Passat available.”

“How’d you manage that? … A Passat? … You’re joking. I saw some classics on the way in. How about a 1951 Plymouth Convertible?” I watched her type faster than I could think; she picked up the phone and dialled some number and chattered something in Spanish.

“Si. Si…” she was saying as I watched another man approach hang up his cell phone.

They talked in Spanish while I leaned on the counter until she pointed to me.

“You want car?” The man asked.

“Yes but I don’t want a Renault or a Volkswagen. I want one of those nice old school convertibles.”

“You know we keep running ourselves. … We … fix ourselves,” he motioned to himself, “They are not original. I have a Mercedes engine in mine. Chevy rear axle. Plymouth gearbox.”

“What kind of car is it?”

“1950 Chevrolet Deluxe.”

“How much?” I asked.

“You’ve been here two weeks right? The writer from Canada? Very cool. We get many like you here. Always sitting by yourself. Smoking and drinking alone all along the beach. That is what Cooba is to you? … No matter. My friend Simon told me sometimes you take the boat too far and he has to come to you? The guy?” he smiled and nodded to the concierge.

“I need your license,” she said.

I spoke close to no Spanish but I could venture a guess what they were talking about. A moral quid-pro-quo. For you see, dear reader, despite the lavish luxury of five-star resorts, the workers themselves cannot partake of any food or drink. They cannot eat, sleep, or relax on resort property. And we, the wealthy, are hard-pressed not to gorge ourselves on the fine rum and cigars and pineapples and steaks and pasta and chicken. One of the maids told me this on the second day. I couldn’t eat for two days. At some point, coughing in cigar smoke, I decided I would take food out of the cafeteria or restaurant under the guise of eating it in my room and then split it amongst the workers. I’m not trying to make myself seem like some paragon of virtue or compassion; it was more for my own comfort than for theirs. You can’t really enjoy your food if the man serving you is himself hungry. By the fourth day most of the crew knew me. In fact, one gentleman named Joseph, which I later learned was pronounced Hoseph, had even gone so far as to bow his head slightly every time he saw me, and after repeatedly begging him not to, he just grinned whenever he saw me.

I slid my license across. “Which guy?”

“The compassionate man. The man with a soul.”

Clichés all over the place. “I don’t believe in the soul.”

“Oh but you should hermano. The soul believes in you! You take my car. I trust you bring it back in one piece.”

“You have my word.” A lie, of course; there was no way I could guarantee jackshit.

He tapped me on the shoulder and walked away, lighting a cigarette.

The concierge handed my cards back and smiled.

“Gracias,” I knocked on the counter.

“De nada,” she handed me the keys. “It’s the last car. It is red. Staff parking. You have to go all the way around. Do you know how to get to Havana?”

“I’ll manage.”

She laughed and shook her head, “Drive down this main road…” she motioned with her hands, “And follow it until you merge onto Circuito and Puente Bascular. Then after a while you’ll get to a sharp left at the bus station and parking area. It’s almost like a U-turn. Then Central de Cuba. You got it? CEN-TRAAAL DEE CUUEEBBAA,” she stretched the last part out.

“I got it.”

“You’ll get to Matanzas. Stay on the coastline. The street is called La Habana. That will be 80 kilometres. Should be an hour perhaps. It’s a nice drive. There are small nice cafés. It’s safe to stop. Then you just… follow signs.”

“My specialty,” I helicoptered the keys in my hand and walked out. But not before buying another box of Cohiba Panetelas from the hotel boutique.

“You driving?” The cigar salesman asked.

“What gave me away?”

“Nothing. You’re The Guy right?”

I was already tired of hearing that.

“… You’ll love Havana. I’m from Mexico myself. Moved here many years ago. My wife is Cuban.”

“Sounds good. We’ll talk later.” I left.

Walking around the side of the building, the sun reflected off the hoods of what could’ve been a history of the automobile arranged from classic American to the newest 2011 Peugeot hatchback. How’d they get those here, I wondered.

I’ll give it to Hector. He had a wonderfully restored red Chevy convertible with a white line going straight from the headlight to the bump of the back wheel. I polished the rims where the chrome met the duo-coloured wheels. The red leather interior still smelled fresh as if it hadn’t been eroded by the passage of time. With a turn of the key, I travelled straight into the 50s.

The concierge hadn’t lied; it was a wonderful landscape, especially when I turned off the highway and drove along the coast. Middle-aged Cubans worked while their strapping young people danced for the busloads of tourists who saw it fit to stop along the water. The only thing that diminished the surreality of continued existence was the constant shuttering sound of camera phones pining to immortalize moments they probably share with thousands of others. My panetela burned smoothly and I was driving against the sun so the darkness burned away with every kilometre I put behind me.

Some people don’t leave the resort the entire time. What’s the point of that?

I pulled over at a café and had something they called an American Destroyer, and when I told them I was Canadian they just laughed and said it would destroy me anyway. It was Havana Club mixed with a pineapple smoothie. I rested while smoking another panetela. Squinting as I watched the sun rays bounce off the red hood of the Chevy.

When it was time to hit the road again I pulled into a gas station to ask for directions because I was afraid I missed that U-turn at the bus station or wherever. I had a coffee. They only drink it black. There are no frappuccinos or foamy flavoured drinks. Things are simpler. The contempt with which the café owner looked at a young German man who asked for milk because the coffee was too strong kept me entertained for hours. I still had ways to go.

Approaching Havana I heard, whether real or hallucinating, the sounds of drums and street parties. I parked before I actually entered the city and rolled the top back up. In the city there was no need for the natives to frolic from store to store and buy things for the benefit of making the tourist feel safe and comfortable. They had, despite their globally morose situation, a deep elation, and though sometimes it was buried in their hearts, you could sense its presence. Most of them didn’t care which two celebrities were dating and at what bars they could be spotted. Seeing random people dance, sometimes couples, wasn’t something I saw every day in Toronto; I berated myself for appropriating their culture; it was unknown to me. New, rich, and full of wonder. I am pampered for even being in this situation and have this thought. They dance; we shop. It’s all the same feedback loop. Was I permitted to elevate their culture, romanticize it? I was sure that there were places here where conditions would be squalid; but then we had those in Toronto too….

It was majestic. There was a street market; tables full of items ranging from family photographs to war medals to car parts being sold for prices that to the capitalist feels like robbery. Little did I know, that despite Havana’s reputation in the west for being a sex-fuelled, boozed, and debauched city, in the corner of my eye hid one of the most profound interactions of my life.

Walking past a table full of handmade trinkets and then another filled with classic baseball cards I caught a glimpse in the corner of my eye. A flashing blur of aqua blue and yellow. When I looked it was only the tame prosaic colours of Cuban tapestry; the dark green army uniforms of the police and the generic grey or black of the merchants. It was too hot and I felt faint. The thirst returned and while I was enjoying a banana smoothie with dark rum I saw it again: the blue and yellow weaving between a few dark green uniforms checking a man’s ID because he was eyeing a collection of used family photos too attentively. I threw too much money on the table venturing to catch the sky but it was she that caught me when she marched up and sat across me. She did not disappoint.

“Bonsoir,” I blurted out, following the sun-ray shining upon the golden waves that formed her hair and down her blue summer dress that rested on her snowy shoulders.

“I saw you drive in and then just now looking at the medals. I love it here.”

“There’s a lot of stuff here.” I saw a plane in front of the clear blue sky and followed it until it approached the sun.

“Not really. That’s why I like it. No stuff. It’s…” she inhaled, “Air. Just air. It’s nice to see you again.” her eyes flickered at my brogue boots. She and I had been more than classmates at the University of Toronto.

“You too. Did you ever go back home?” It was more than nice to see her again.

“Yep. To Oslo,” her smile made the sun blink, cooling the weather when clouds covered it.

“That’s a long way.”

She talked about Cuba as if she was a native and it was beguiling to hear her voice. Those hazel irises contracting and dilating talking about Che and Sartre’s visit and Fidelito—that was what she called him. She hated him but spoke of jingoism and illegal embargoes and unjust sanctions in subdued tones lest we be overheard by a nosy soldier. Every time she pushed a strand of her golden hair out of the way the sun shined on her face for a second and lit her up even more. I was lost. She talked about the fact that the Hotel Nacional had opened on New Years Eve in 1930. I’d never had patience for people talking but she was…. That’s it, she simply was. Another cliché. I left the rest of my drink when she told me that’s where she was staying and invited me back to see the view.

She had a suite all to herself. It felt magical to see the graffitied walls of that Matanzas village, but then the view of the Havana Harbour, steps away from where Sartre, Sinatra, and the Duke and Duchess of Windsor had stayed, relegated that graffiti to historical shame. In fact, looking out the window, I could see the rich tourists across Cubans trying to sell them fake Cohibas with no discernible difference between them. They all looked so small, like ants trying desperately to understand what it was that kept them moving and circling themselves. A breeze caught my hair and I felt the cool air on my face.

“Beautiful isn’t it? I love Cooba,” she never quite pronounced it as we do: Queba. Rather, with that slender and sexy North European accent trying at the same time to pass for Spanish. It was Cooba. Habbana. Ron and Soeda. Falling in love with beauty is the easiest thing in the world. You can fall in love with someone’s beauty in the morning and cease to be in love by dusk. In that hotel, years after we’d parted ways as lovers, I began to love her not for her beauty but for her soul and her manifestation not as a being of beauty but as a being of meaning. No self-help book, entrepreneur keynote, designer boutique or Apple Store or reasonable rate of return could give me the gift that Cuba gave me. It felt so natural and so real and yet so transcendental that the city, so different from home, in which this feeling occurred would have profound meaning for the rest of my life.

She poured us drinks from the minibar and talked about the different kinds of rum cocktails they make there. It is a fallacy that only a native can understand and feel a culture and land. In other words, the claim that an expatriate or wanderer could never attempt but to scratch the surface of the beauty of a particular place in vain is simply not true. Contrary to earlier, I now thought that travellers always have a unique perspective at their disposal. They are free of bias if they take care that nothing first-worldly has happened to them to provoke a bias, such as losing their luggage or being delayed on a first-class ticket. Naturally, if the person is a frequent wanderer; a flâneur, their judgment may be amplified for they have an abundance of comparisons to rely upon. I wouldn’t know Cuban cigars were superior to Dominican ones unless I’d been to both places or tried them both. What a terrible example, but you understand what I mean. Critics will say there are preferences and the wanderer will have to agree. New York is better than Havana. Thus criteria are established to judge a place not by its own merit but by its comparison to other cities that fit those criteria. To curtail the argument that the notion of a beautiful city, like the notion of a beautiful man or woman, rests upon the objective, the wanderer must relinquish all previous moments except the moments that occur in the destination. In other words, to presume nothing but the experience itself. This is a posteriori.

Why was I trying to think so logically? To deduce some philosophical system out of rich people travel and spend money and romanticize the natives’ lives?Every book a white man writes about Africa is the same book with the same clichés. Now I was guilty of this.

“Isn’t it amazing?” she came up behind me and we stood side-by-side staring out into the harbour.

I looked at her up and down breathing the same air as her and for a moment, that insatiate thirst was quenched.

“Oh my god! I forgot you were a writer! I have to take you to Hemingway’s. Grab your shirt.”

“I’ve already been. There’s one in Helsinki.”

“Not like this one,” with that floaty step of hers; the dancer’s step, and that smile that lit up the sun, I had no choice but to follow. The clichés nearly broke me, I thought, but then I shrugged; you have nothing better to do, I told myself.

And in the abyss of Hemingway’s I drowned. She chattered with the owner in broken Spanish and pointed to me. I glanced around at all the pictures of Hemingway with various Cuban political and social figures and narrated the stories behind each picture to myself. She was telling him I was a writer or something and like a ritual, as if he’d done it thousands of times before for those western tourists interested in Jazz Age literature and the surfaces of their country, he began mixing a drink.

“No,” I interrupted, lighting a panetela, “Give me something else. I don’t want what Hemingway drank,” it was only sprite and white rum anyway. “Make me something distinctly Cuban. Distinctly yours.”

A frightening smile washed across his face as he began mixing a cocktail like an old master coming out of retirement for one last job. “This,” he pointed to the glass, “La Generación Perdida.”

“What’s it mean?” I took the glass.

He smirked, “The Lost Generation.”

Every generation thinks they have it rough. But one financial meltdown after another, one corporate bailout after another at our expense, and you find yourself expecting the next one rather than hoping or looking for a saviour.

The next thing I remember is waking up in her hotel room and watching the water through the window.

“What was in that drink?” she yawned with the sun-rays reflecting from her hazel irises through the window and into my soul.

“I don’t know. But it lost me all right.”

“Now you know how they feel,” she turned away from the window and covered herself with the blanket.

To this day, whenever I play this conversation over and over again in my head in ardent nostalgia, I don’t know why I asked, “You want to come to Varadero with me? I’m heading to Europe after.”

“Where in Europe?”

“Paris, then catching the plane to Lisbon.”

She just laughed as she got dressed. “Maybe next time, my love.” She left the room to get breakfast and never returned. I waited three days. I wanted to stay indefinitely but my hotel called. They were worried and reality set into me like the darkness of those clear night airs so seldom felt in Canada but so plentiful on that “magical” island.

“Thanks Hector,” I shook his hand and handed him the keys, “I filled her up for you.”

“You look different. Believe in souls now, hermano?”

I didn’t answer as readily as last time, “Thanks Hector,” I repeated in an attempt to ignore him, “She really is wonderful,” I pointed to the car.

He laughed. “She is… I like you hermano. You’re cool.”

I bowed to Joseph and left that day. What was it about that place?

The same uncanny disquiet shook me when I saw her again. It was in Paris and I’d been thinking of her constantly. Like the second act of a bad film, I’d dreamt we’d moved to one of those coastline villas outside of Havana and we would wake and drink black coffee and stare out into the sea. I was writing her a poem about it while having my breakfast at the Plaza Athénée and she just… walked in front of me.

“This place is nice,” was how she greeted me after all that elapsed time, “But it’s no Cooba!” then she bent down, pecked me on the cheek, and walked towards the lobby. By the time I chased her outside she was gone again.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

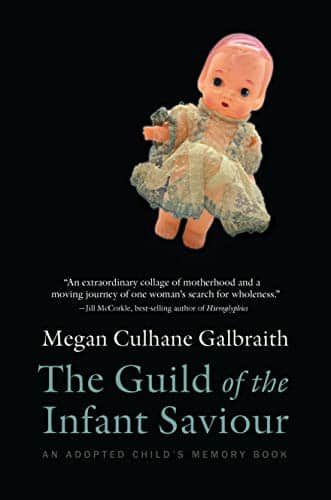

Megan Galbraith is a writer we keep our eye on, in part because she does amazing work with found objects, and in part because she is fearless in her writing. Her debut memoir-in-essays, The Guild of the Infant Saviour: An Adopted Child’s Memory Book , is everything we hoped from this creative artist. Born in a charity hospital in Hell’s Kitchen four years before Governor Rockefeller legalized abortion in New York. Galbraith’s birth mother was sent away to The Guild of the Infant Saviour––a Catholic home for unwed mothers in Manhattan––to give birth in secret. On the eve of becoming a mother herself, Galbraith began a search for the truth about her past, which led to a realization of her two identities and three mothers.

This is a remarkable book. The writing is steller, the visual art is effective, and the story of what it means to be human as an adoptee is important.

Pick up a copy at Bookshop.org or Amazon and let us know what you think!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Anti-racist resources, because silence is not an option

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~