CW: suicide, attempted suicide

The psychiatric clinic just on the outskirts of Paris was very posh: a restored sixteenth century stone exterior that reminded me of the relais—country houses—that aristocratic families built when they wanted to get away from the monarch’s court. The clinic’s lobby and dining rooms were beautifully appointed with expensive furnishings. My psychiatrist had recommended I stay there for a couple of weeks to receive treatment for my worsening depression.

I had one of the largest patient rooms. A bedroom big enough to waltz in, with the northern light coming from the floor-to-ceiling windows. Private bath. Embroidered bell-pull if I needed anything from the staff. The shrinks came to talk with me once a day. I lied to them about how bad I was feeling, not wanting to admit what an idiot I was for still living with Michael. I only wanted to get back to the Paris apartment to make sure Michael wasn’t sleeping with men in our bed. After everything that had happened, I knew I shouldn’t give a damn, but I did. My real therapy was painting.

I pulled up a dressing table to the window where I began an illumination of St. Francis taming the wolf. I was thinking of the medal I’d given Michael on our trip to Assisi, the one he said the mugger had stolen, another one of his lies. What was I trying to work out? Did I want to replace the lost medal with my artwork? Or could it be that I wanted to be like St. Francis, using love to tame the wild wolf, to domesticate my roaming husband and lure him back to my home and heart. St. Francis was Michael’s favorite saint, and though I couldn’t replace the medal, I thought an illumination would show my love for him. Anything to bring back the version of the man I still loved so much. Unsure of what I hoped to achieve, I started drawing it anyway.

I knew I didn’t want to be alone. So, I called a friend. “Beth, I’m in a psych clinic in Paris. Can you possibly come be with me?” I asked. “The doctors are dismissing me this weekend. I gotta get out of here.”

I so needed to be with a friend who knew both Michael and me. Beth had stayed with us many times in Paris. I’d told her of Michael’s affairs with young men, prostitutes who only wanted his money—my money that my parents had put aside and left to provide a secure future for me and my husband. She knew how devastated I was. We talked several times a week, and I poured out my outrage and grief to her.

“Of course, I’ll come. Matter of fact, I can stay for a week.” she told me. “How are you coping? How long have you been in this clinic?”

“Not doing too well. Michael hasn’t been to see me,” I said, trying not to cry. “He hasn’t even called. I’ve been here over two weeks—I gotta go home.”

“Stay put till I get there,” she said. “I’ll book a hotel near your apartment and you can stay with me. Before I come get you from the clinic, I’ll go by your place and see what’s up with Michael.”

***

“Have you been outside today?” Beth asked, hugging me when she got to my room. Her long blonde hair brushed my cheek. “Gorgeous weather, but cool. C’mon—you need some sunshine.”

I passively allowed her to swaddle me in blankets. There was a large terrace at the clinic where patients and visitors could view the Paris skyline, the Eiffel Tower, and Sacre Coeur. Better digs than my apartment, whose view was nil. It was “sous-sol,” meaning it was between the ground floor and the basement. It had originally been a coal cellar. From the clinic’s terrace I saw flowering trees, tulips below bursting from their winter solstice. Peace. Tranquility. New life. Maybe even hope.

“Did you go by the apartment?” I asked her. “Did you see Michael?”

Beth looked down, couldn’t meet my eyes. “Yeah. Apparently, he just woke up. He met me at the door with only a sheet tied around him,” she said. “The floor was a mess of other sheets, rumpled clothes, liquor bottles, and used condoms. We saw them at the same time. He looked at me defiantly.”

Beth said to Michael, “I thought you told Diane you wouldn’t be sleeping with men anymore.”

He said to her, “I never said that. I told her I wanted to stay married to her. Beth, I love Diane. But she’ll have to accept my new lifestyle.”

Then she turned to me, and asked kindly, “Are you okay with that? How d’you feel about going back there?”

“I’m not okay with that,” I said wearily. She was standing in front of me, leaning on the terrace bannister, and partially blocking my view of the Eiffel Tower.

“What’re you gonna do about it?” she asked. “How can you stop him?”

“I dunno yet,” I said.

“You wanna divorce him?” she asked. “Or at least, a separation?”

“Sure, I’ve thought about it,” I said, looking down at my hands, wringing the corner of a blanket. “But where would I go?”

“Why the fuck should you go anywhere?” she cried, defending me. “Boot his sorry, cheating ass out the door!”

“I can’t.” I felt defeated. “I keep thinking I can make our marriage work, if I can just hang in there,” I persisted. “I don’t want to live without him.”

“But you can live without him,” she said. “You’re so much stronger than you think you are.”

I had issued an ultimatum to Michael during one of our counseling sessions. “If you continue to have these affairs, it’s over.” He only shrugged, as if to say, “What are you gonna do about it if I do?” I was coming to terms with the fact that I had no boundaries and Michael knew it too.

A week or so later, we had tickets to a piano concert in Paris. Michael was especially complimentary of my appearance that evening, declaring his oft-repeated remark about how proud it made him feel to be with me. Each of these compliments boosted my ego, my belief that he loved me, that perhaps things could and would change.

“My god, you look stunning tonight!” he said.

Even though it was considered bourgeois to “dress” for concerts, operas, art openings, we had always loved dressing up, and saw no reason to quit just because it was the current Paris fashion to wear jeans everywhere. I’d taken great care with my makeup, even putting a shimmery stroke of highlighter on my cheeks and collarbones. I wore a sheer, gold and silver embroidered, navy silk tunic over a navy tank top and leggings. I did look stunning!

In the taxi, he casually mentioned that he was going to Cologne for his boyfriend Voss’s twentieth birthday party. “I’ll be gone for the weekend, but I’ll be back on Monday,” he said.

I knew who Voss was—I’d seen his picture. He was Jordanian. Michael had rhapsodized about him more than once, often in the same sentence when he’d gushed about Tristan, his lover in Canada. My whole body stiffened, but I finally managed to say, “No, you’re not going. You can’t keep doing this to me!”

“Oh Diane, stop with the drama.” He looked out the taxi window, bored, but not upset. “I told Voss I’d be there—he’s counting on me.”

I asked the driver to stop. “Enjoy the concert,” I said to Michael. Getting out, slamming the door, I hailed another cab to take me home.

***

Our apartment was blessedly still, peaceful. I felt a sense of incredible relief wash over me like a cool breeze. The sense of stiffly and stoically holding it together was gone. I was alone and it felt so delicious and sweet, and it didn’t hurt that the spring Paris night smelled of lilacs.

I filled a large pot with salted water for pasta and turned on the gas burner, remembering nostalgically, when we were renovating the kitchen, how I’d stood my ground on getting a gas, rather than an electric stovetop. Michael loved my cooking.

“No one who cooks worth a damn,” I said, “cooks with electricity. You can’t control the temperature or the timing!”

“It’s gonna be way too expensive,” he argued. “Our building’s not fitted out for gas.”

“So, we’ll be the only ones who have it,” I said.

“I can’t justify the expense,” he said.

I played my last card. “Fine,” I said, “then we’ll eat all our meals out—I’m not cooking on electricity anymore.”

“Okay, okay. I give,” he said, throwing up his hands. “But you better crank out some pretty amazing dinners.”

***

As the water heated to boiling, I went through the hall closet and bathroom pantries grabbing every anti-depressant, every prescription painkiller and sleeping medication I could find. I also picked up Michael’s prescription meds. Had to make more than one trip in order to get them all. Bringing them to the kitchen, I spread them out on the granite countertop. There were a lot. I added fresh fettuccini to the boiling water.

Filling a large water glass, I calmly took every pill.

I’d accomplished everything I wanted to do, and what I hadn’t done wasn’t all that important. Our parents were dead. The Michael I had married was forever lost to me. My son Andrew was settled in his own happy life with his wife and kids. Sure, he’d miss me; the boys were little—they’d forget me soon enough, and I wouldn’t be a burden to anyone.

It was a quiet, rational decision: my wonderful fairy tale marriage had turned into a Stephen King horror film, and I didn’t know how to escape from it. I was numb. I felt no self-pity, no thought of punishing Michael. I just wanted out and could see no other way. I didn’t write a suicide note—didn’t feel the need for melodrama.

By the time I’d taken all the pills, the pasta was ready to drain and season with cold-pressed virgin olive oil. I even added freshly chopped Italian parsley, expensive sea salt, and ground white, black and pink peppercorns. If this is gonna be the last thing I eat, it should be good.

I had done my research well—had googled “how to suicide” and discovered that unless pills were taken on a full stomach, they would likely be thrown up. I wanted to be sure I was successful.

Thinking I had time to die gracefully, I enjoyed my pasta, and didn’t rush to throw away the empty pill bottles. I was eating my last mouthful, feeling rather smug that I had pulled this off, when I heard the front door open. Just as Michael came in, I passed out on the kitchen floor.

I vaguely remember the EMTs cutting open the front of my fabulous, expensive Ralph Lauren tunic, thinking, please don’t ruin it! and being carried to the ambulance, but nothing more until I woke up from a coma four days later in the ICU. “No,” the nurse said when I asked. “Your husband hasn’t been here to see you.”

***

“The cops came to arrest and question me!” Michael fumed when he picked me up at the hospital. “They wanted to know what I’d had to do with your attempted suicide. Can you believe that? I was at the police station for nine fucking hours!”

“Sorry,” I mumbled, even though I had nothing to apologize for. “Why would they do that?” At this point, my sympathy for his arrest was about as real as his sympathy for my suicide attempt.

“They thought maybe I’d poisoned you, or urged you to take all those pills,” he said. “They even asked me if money was involved.”

“So, what’d you tell them?” I asked, not really caring, and still groggy from the meds they’d given me before I left the ICU. I just wanted to sleep again.

He shrugged. “I told them I loved you even though I was gay, and would never want you dead,” he said. “The first thing I did after I got back home was to call Andrew and all our friends in the States.”

“To tell them I’d failed at suicide?”

“That, and to let them know I was gay again,” he said, “even though I wanted to stay married. Funny, no one seemed surprised.”

“What’d Andrew say?” I asked.

“Said he’d figured I might be gay—had thought so for a year or two ‘cause I wasn’t paying as much attention to you as I had before,” he said. “How I was always going off without you. He was really cold to me when I told him about the police crap.”

Maybe that’s because you seem a lot more upset about being questioned by the police than the fact that I almost died, I thought. You narcissistic, self-centered little shit.

“Did he ask how I was doing?” I ventured.

“Yeah,” Michael said. “I told him you were out of the woods, that he didn’t need to come to Paris. Maybe you oughta call him—let him know you’re okay.”

But I’m not, I thought. I tried to kill myself and you don’t even give a damn.

***

My suicide attempt left me feeling like my blood was icy; my heart a dull beating rock. I felt so cold and alone. Michael was no help to me. He was drinking himself into a stupor on a regular basis. I picked up the phone and called David, Michael’s alcohol therapist.

“David, please,” I said, “I just got out of the hospital from a suicide attempt. And I don’t know who else to turn to.”

“Are you okay?” he asked.

“Alive, but still really traumatized,” I said.

“I don’t usually work with the non-alcoholic partner in a relationship,” he said, “but because the alcoholic Michael is so closely linked to your own trauma, I’ll take you on as a client.”

My dead heart leapt a bit. Was there some life left in me? Some spark that Michael had not extinguished with his constant cheating, indifference, and boozy nights of horror?

I felt hopelessly stuck, doomed to stay in a sham of a marriage that was making both of us utterly miserable. Why? Because I had convinced myself that I couldn’t live without him. But that deeply flawed thinking had gotten us where we were: Michael had once tried to kill himself because, being gay, he couldn’t see himself in a straight marriage for the rest of his life. And I had tried killing myself because I couldn’t live in a marriage where my husband was having gay affairs.

Nothing I had done to try to fix our broken marriage had worked. Michael had decided he was “gay again,” but the truth was he had always been gay. Instead of trying to get him to give up his lovers and struggling to make him love me the way I needed to be loved, it occurred to me that maybe I should try to love myself, to save myself.

When I finally decided to change my life, everything changed. The smell of the air, the feel of my jacket, tight around my body. Food tasted better. The sun was warmer. The wind windier. Everything had new power. This is what happens when a co-dependent person separates from the source of their dependency. Of course, I felt scared, but there was this intoxicating freedom moving inside me, overshadowing the fear. I sprouted wings and new legs. I had ideas, I was full of life itself; all my old life had been sucked out of me. I felt, again, alive.

***

I called Andrew to tell him I was leaving Michael. There was silence on the crackly line and then he gave a sigh.

“Mom, I’m glad you’re divorcing him—just wish you’d made the decision a year ago. I love Pops,” he went on, “but you’ll be so much better off without him.”

“But I’ve never lived completely by myself,” I said. “The very thought of it scares me. I’m not sure of what I’ll do, or where I’ll live.”

“Mom, remember the last line in Mame? ‘Life is a banquet, and most poor bastards are starving to death.’ ”

“I remember,” I said, laughing through my tears.

“Well, keep repeating it to yourself. You’ve got the whole rest of your life to live and enjoy,” he said. “You survived your side of pasta, but Mom, you haven’t even gotten to the cheese course in this banquet!”

Her publishing credits include Angel et Démons dans la Littérature du Moyen Âge (Presses de L’Université de Paris-Sorbonne,) Mon Coeur Qui est Maître de Moi (Editions Alternatives,) and Tournaments Illuminated (Society for Creative Anachronism)

***

Wondering what to read next?

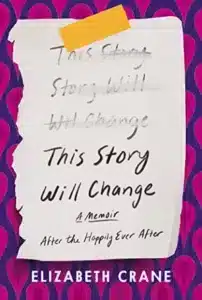

This is not your typical divorce memoir.

Elizabeth Crane’s marriage is ending after fifteen years. While the marriage wasn’t perfect, her husband’s announcement that it is over leaves her reeling, and this gem of a book is the result. Written with fierce grace, her book tells the story of the marriage, the beginning and the end, and gives the reader a glimpse into what comes next for Crane.

“Reading about another person’s pain should not be this enjoyable, but Crane’s writing, full of wit and charm, makes it so.”

—Kirkus (starred review)

***