The acclaimed author talks about how we all navigate, experience, bear life and because she is looking into my eyes on Zoom and because she—her talking, thinking, working image—is in this room with me, I know she is speaking directly to me. I latch onto the word bear. That’s it. That’s what I’m doing right now, bearing life, bearing art, bearing the chill in this room.

Her earrings swing, her shelved books on the neatly arranged bookcase applaud her. She speaks about unbearable scrutiny of herself. Another attendee, an editor I recognize, who is brave enough to have his video on, laughs, his head doing the friendly tilt and his shoulders the mirthful squeeze upward. As she speaks of the metaphysical nature of her concrete words, the word bear bear bear runs through my head. When I write it down, I conjure Goldilocks, who in her charming quest for perfection, did not win what she wanted. Maybe it’s spelled unbareable, the emphasis on the nakedness of emotion, but no, it’s bear.

Another person pops up in the row of boxes neatly framing the acclaimed author. I recognize this recent attendee’s face, admire her red lipstick, the streak of blond pushed off to the left. Her name—I know it! She, too, is an author, an accomplished one, whose stories I read more than once and will continue to read. I watch her reactions to the presentation, trying to decipher something unspoken, but unable to interpret anything except her wide genuine smile near the end.

On this platform, no one is sitting in the front row, and no one is whispering behind me. No one can see my hair piled up in a bun without aid of a mirror, frizz framing my face, my comfy house pants with the hole in the knee. I don’t have to reveal my reactions, my attention or my inattention. My presence hovers in a black box with my name in white letters.

I have not traveled far to be here, only from dinner table to desktop. The acclaimed author traveled to her study, along the bandwidth echoing within the interlaced highways and byways of her computer to my screen. This is an easy, one-sided connection that requires little of me physically.

Is there part of me that has travelled to her? To each attendee’s place? Are we crisscrossing the internet nether land to arrive in each other’s spaces.? Do I have a part of each person in my space? The weight of my impending or impossible future is as painful as yours. Isn’t it? Isn’t this what we are trying to understand? We are bearing life’s unanswerables together, each giving and taking and receiving words, weighted and full, their ethereal presence filling each of us.

Wondering what to read next?

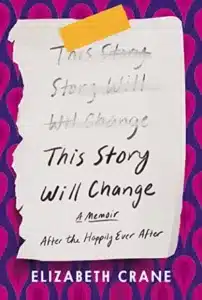

This is not your typical divorce memoir.

Elizabeth Crane’s marriage is ending after fifteen years. While the marriage wasn’t perfect, her husband’s announcement that it is over leaves her reeling, and this gem of a book is the result. Written with fierce grace, her book tells the story of the marriage, the beginning and the end, and gives the reader a glimpse into what comes next for Crane.

“Reading about another person’s pain should not be this enjoyable, but Crane’s writing, full of wit and charm, makes it so.”

—Kirkus (starred review)

***

The ManifestStation is looking for readers, click for more information.

Your voice matters, now more than ever.

We believe every individual is entitled to respect and dignity, regardless of skin color, gender, or religion. Everyone deserves a fair and equal opportunity in life, especially in education and justice.

It is essential that you register to vote before your state’s deadline to make a difference. Voting is crucial not only for national elections but also for local ones. Local decisions shape our communities and affect our daily lives, from law enforcement to education. Don’t underestimate the importance of your local elections; know who your representatives are, research your candidates, and make an informed decision.

Remember, every vote counts in creating a better and more equitable society.