My son and I stand on the driveway bundled in blankets and staring at the sky above us. It is the Blood Moon Eclipse. Astronomers tell us an event precisely like this has not been seen in 580 years. He set an alarm for 3:30am to watch it happen and opened the door of my bedroom to pull me from the edges of fuzzy sleep and stand here alongside him. Our feet are cold on the concrete, and we stand side by side. We are alone with no one else awake at this hour to watch. The edge of the moon is bright like a crescent, the rest of it shaded a deep red. I stare at the shadowed shape beyond nearly empty November branches. I let the silence settle around us, and “Wow!” is all he can say, eyes wide. “Mom, just look.”

My son is twelve and obsessed with all things science. He reads biographies of famous scientists, watches YouTube explanations of scientific concepts, and has his own laminated copy of the periodic table. Among this fascination for science lies an overwhelming attraction to the cosmos. The swirling galaxies of stars and planets, the little we know and the long list of things we don’t yet understand. I wake with him at 3:30 to see the eclipse because I have learned through his eyes to see the phenomena as he sees them, vast and mysterious and endlessly interesting.

I have a photo of my own father when he was my son’s age. Freckles scattered across his nose like stars, a chip on his tooth as he smiled, eyes shining through the veil of the glossy, sepia-toned paper and across the stretch of decades between this moment and that one. Like a scientist, I look for clues connecting his DNA with my son’s. Their eyes, their hair, their searching spirits stretching backwards and forwards and through the blurry hands of time. I wonder if the two of them can somehow find each other across the swirling cosmos.

We talk about the universe, the stars, the moon, and the space in between. At the dinner table, driving down the road, packing lunches, as we place piles of folded laundry where they belong. My son asks me what I think about these unknowns, explaining to me what he believes and the connections he makes between all of his reading and watching. Last year, his favorite topic was black holes. By the end of the summer, he knew more about them than I’d ever cared to know and would prattle endlessly at me explaining as I half-listened, getting lost in his wordy explanations and listings of facts. “Did you know, Mom, that black holes can be millions of times heavier than the sun? Black holes are born when a star dies and explodes on itself, and then the hole just grows bigger and bigger.”

I watch him grow bigger, too. His shoulders broaden and he grows taller everyday. I watch the baby cheeks fall off his face and the jaw become more defined. I watch him reading his science books in the living room with his long, bony legs folded up beside him on the couch. I watch him as he begins to understand sarcasm and laugh at the same jokes that I do and as he begins to spend more time alone. I watch the space between us change shape and become larger as he grows.

I chop vegetables at the kitchen counter while my son explains again the process of exploding stars creating black holes. I make piles of red peppers, onions, and tomatoes, organizing them in separate stacks, while he tells me about what cannot be categorized or fully understood. “Black holes are invisible,” he explains. “But scientists know they exist because they can bend light, and then in space, people can see the light around them.” He leaves me thinking about exploding light and expansive voids, and my imagination finds itself squarely back in 1986. My father, with his unexpected accident like an explosion on the constellation map of my life. His end wasn’t the slow fade of a long life well lived, but instead a human star eclipsed in a moment of cosmic surprise. Not a gradual end but an explosion of light like a firework, a flame folding in on itself over and over until you cannot see it anymore. A gravitational pull, my father’s short life has bent the light around it for decades so that I know it’s there even as it isn’t.

When I held my son for the first time, the veil was especially thin, though I wasn’t ready for it. A moment that felt heavier than the sun. Studying his face, which was entirely new to me but somehow also entirely known, the light bent around us. We fell into some place, the two of us, squarely in this hole that I have been swimming in and out of ever since, the place where I stand as a binding thread between a boy and the grandfather he never met. As my son grows through ages and phases, I swim with the current of what could have been, wondering what they’d think of each other, what they’d say if they were to meet.

Months ago, I took a quick snapshot of my son on the morning of his elementary school graduation. He wasn’t ready for the camera, so I didn’t get a posed smile but instead a glance somewhere beyond where I’m standing. He looks solid and true and squarely in the middle of that space between boyhood and manhood, galaxies before him and unknown paths ahead. My older cousin saw the photo and sent me a message. Wow. The first thing I thought about when looking at this photo is your father. I see traces of your dad in him here. I see him here. I just wanted to tell you that.

I swallowed the knot in my throat and did the exercise I have done a million times before, put their photos back-to-back in my phone camera roll and flip repeatedly between them. Dissecting the faces. Eyes, nose, hair, mouth. Nothing is precisely the same, yet there is something there, the star folding in on itself. He asks me, “Did you know black holes don’t even have a surface, but the gravitational pull is so powerful that nothing can escape it, not even light? It’s like they are just emptiness, but they are powerful.” And when he sees my concentration on something else or my thoughts far away, he’ll add, “Mom? Are you listening?”

I’m listening. My father is not here to see us standing on the driveway with our sleepy eyes and bed hair, huddled in blankets, staring at the shadowy moon. But then again, he is. The light bends in a way I can see with my heart if not my eyes. I have so few things of his, but I do have his old copy of the Bhagavad Gita, a work I cannot read cover to cover because it is as overwhelming to me as the cosmos. It tells me death is as sure for that which is born, as birth is for that which is dead. Exploding stars don’t return to nothingness.

There is so much I will never understand, both about the cosmos and the small and particular life I was given. As we stand on the driveway, bundled in blankets and staring at the sky above us, I marvel at the moon and the sun, the golden November leaves hanging on the branches, stars, fire, memory and time, the oldest trees, rolling mountains, the deep ocean, the infinite space in front of us, how small we are but these lives are all we know. Maybe my father is there somewhere, watching us across the stretch of space and time, or maybe instead he is right here in the space between us where the light bends. I feel my cold toes and folded arms, the weight of silence as we stare. I watch my son’s bony frame angled to the sky, his hair resting on his forehead, his searching eyes, the pull of empty space holding the whole universe together.

*this piece appeared previously in Braided Way Magazine

Katie Mitchell is an English teacher who lives in suburban Atlanta with her two children. Her work has previously appeared in Yellow Arrow Journal, The Appalachian Review, HerStry, Braided Way Magazine, and Huffington Post, among others. She is endlessly curious about the ways the natural world mirrors our internal landscape. A seventh generation southerner, she is currently at work on a memoir about grief for both people and places that are long gone. You can find her occasionally on Twitter or Instagram @mamathereader.

***

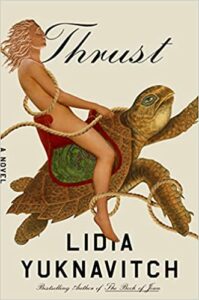

Have you pre-ordered Thrust?

“Blistering and visionary . . . This is the author’s best yet.” —Publishers Weekly (starred review)

***