by Joy Riggs

Elias packed everything he needed for eight weeks away at college, and Steve helped him stow it all in the trunk of my car. Everything except the bean bag chair, which they smushed into the right rear passenger seat. The trunk contained a plastic laundry basket brimming with bedding for an extra-long twin bed. A suitcase packed with spring clothes and a few sweaters. Books, new spiral notebooks, a desk lamp, classical piano music, plates and utensils for in-room dining (the cafeteria still under a pickup-only operation). A laptop. Three bottles of allergy medication. A fan, which Elias had deliberated about – how hot would it get by the end of May? He wasn’t on campus last spring, so he didn’t know.

The trees in our yard stood tall and bare, ready for new buds to emerge. The snow was gone. Elias left his winter coat on a hook inside the house.

After he hugged his brother, who was staying back with the dog, Elias buckled himself in next to the bean bag chair, and we set off on a four-hour drive, grasping the welcome chance to inject some life into what remained of his sophomore year.

Forty minutes into the trip, Steve realized he’d forgotten his sunglasses. He was usually uber-organized when it came to vacations, but we weren’t used to traveling anymore. The opportunity to plan this overnight trip had made him almost giddy.

“There are some plastic sunglasses in the driver’s side door, if you need them,” I said.

Ahead of us, the afternoon sky was a dull gray; rain seemed more inevitable than sun. I turned my head to look back at Elias. His long fingers were tapping out a rhythm on his knee.

“Have you thought of anything you’ve forgotten?”

He paused. “I might run out of toothpaste. I have a few travel-sized ones,” he said.

“Well, if that’s all you’ve forgotten, you’ve done well. That can be easily remedied.”

Elias was the youngest and most organized of our three children. But I never thought of him as “the baby.” He’d always seemed like an old soul, from the he emerged at the hospital, with his shock of sandy brown hair, clear blue eyes, and laid-back demeanor. Although most people said he looked like Steve, he reminded me of me, personality-wise. Responsible, steady, high-achieving but modest. Slow to anger – in fact, had I ever really seen him angry? Not for years. He grew up being talked over by his older sister and brother; when he made the effort now to speak up, it was usually because he had something thoughtful to say.

The rest of the drive was uneventful and drizzly. That evening, we met up with Elias’s girlfriend, Nameera, and ate dinner outside in the 40-degree weather, preferring to risk frostbite over COVID. The next morning, we chose “grab-and-go” items from the hotel breakfast area and ate them in our room.

I felt like I should say something meaningful, but after sheltering together for twelve months of the pandemic, what more was there to say?

“I’m really proud of you. It’s been quite a year,” I said.

“Yeah, it’s been strange,” he said.

Tears formed in my eyes, so I changed the subject.

“How did you sleep last night?”

“I had trouble getting to sleep at first,” he said. “I’m really excited.”

At the campus center, he picked up a room key and a plastic bag stuffed with snacks, hand sanitizing wipes, and a face shield – essentials provided by the college. What had they given him at the start of freshman year – a lanyard, a water bottle? It was hard to remember now. He made two trips to carry everything from the car to his dorm room; we weren’t allowed to help him.

When he returned to say goodbye, I pulled out my phone. “Can we get a picture? And can you take it? Your arms are the longest.”

The three of us squinted into the morning sun, and he snapped a picture for posterity.

“I love you,” I said, as I hugged him.

“I love you, too.”

Steve and I walked back to the car, wiping tears from our eyes.

“It actually seems harder saying goodbye this time,” I said.

“I know, that’s what I was thinking,” Steve said. “Why is that?”

As Steve and I drove out of town, I stared at the trees. A derecho had struck Iowa in August, and the damage inflicted by the straight-line winds was still apparent. Trees with their tops shorn off, as though snipped with a giant scissors. Trees stripped of branches and bark. Trees bent in half, as though bent over in grief.

Yet, against the backdrop of trees and dormant farm fields, I also spotted life: cows in pastures, raptors soaring overhead, songbirds flitting across the highway. A gentler wind was blowing. We were on the cusp of spring.

JOy Riggs’ essays have appeared in numerous publications including Toho Journal Online, Topology Magazine, and Peacock Journal. She lives and writes in Northfield, Minnesota. Joy is the author of the nonfiction book Crackerjack Bands and Hometown Boosters: The Story of a Minnesota Music Man.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

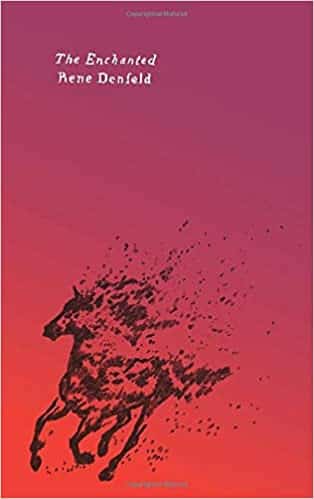

Margaret Attwood swooned over The Child Finder and The Butterfly Girl, but Enchanted is the novel that we keep going back to. The world of Enchanted is magical, mysterious, and perilous. The place itself is an old stone prison and the story is raw and beautiful. We are big fans of Rene Denfeld. Her advocacy and her creativity are inspiring. Check out our Rene Denfeld Archive.

Order the book from Amazon or Bookshop.org

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Anti-racist resources, because silence is not an option

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~