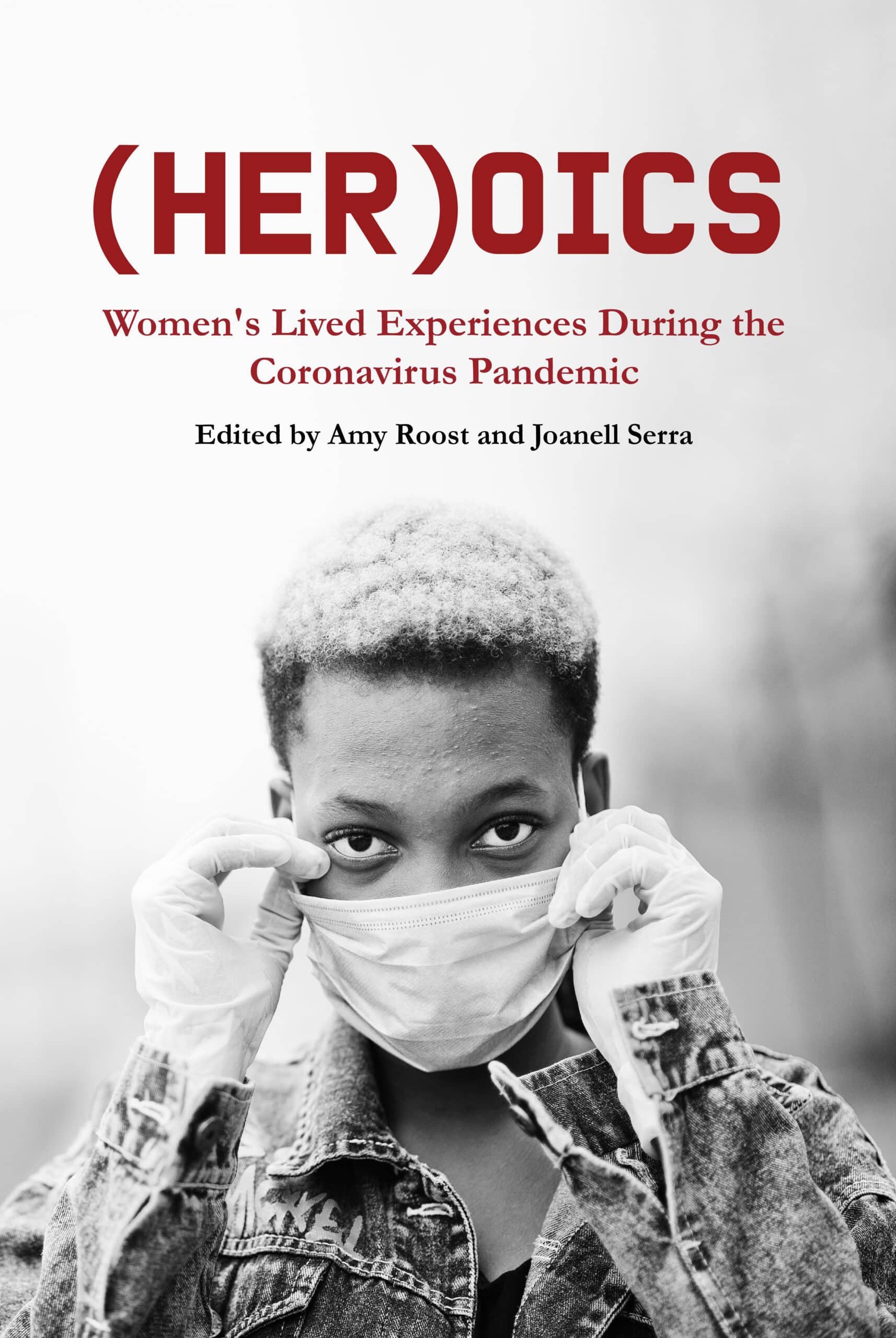

by Marni Berger

Our sense of humor isn’t so dark. We didn’t morbidly plan Leo’s vasectomy for the Friday before Father’s Day weekend, so that it can hover over the day like a cloud, preventing him from not only becoming a father again, but also from doing much of anything that weekend besides rest.

The decision itself is made closer to Mother’s Day, which is also fitting: I will never again have a baby growing inside me. But despite the resolution, my uncertainty rears its head as an identity crisis. What’s certain to me is that eliminating the possibility of pregnancy and motherhood, after nearly five years of both, will mean I won’t know who I am.

***

We talk in circles here and there over the span of a few nights before Leo makes the appointment. My head spins for days, as though we only just decided, even though we really made this decision while I was most recently pregnant, almost a year ago—after my second round of hyperemesis when I was unable to move for five months without vomiting, when I lost my job, as I did with the first pregnancy; when I nearly lost my mind; when, on Halloween night, Leo stood in the dark beside the bed, as I curled into a ball on top of the covers and asked him to call an ambulance and his shadow said slowly to me, “We don’t have to do this, you know.”

But we did do it, the pregnancy. And the result—which is our second child, Frances—has bloomed out a tormenting equation in my mind whose solution I’ve yet to explain: if you add isolation to indefinite suffering, you get the kind of blinding beauty that incites amnesia. Frank, as we call her, just like her older sister Mona, is the sun that has blighted the night. It’s difficult for me to close the door to any more of that kind of light. And the ability to create it feels like the stuff of God.

(Isn’t it?)

But with each child, it’s been more difficult to forget the pain that created her. And so here we are—

The night we finally decide, Frances is ten months old. I look up at Leo in the pixilation of dusk when I say, almost apologetically, “When I was a little kid, I always thought I would have three kids when I grew up.” When he looks at me pained, I look down and mumble like a child, “Not only two.”

He sighs. Leo is standing in his t-shirt and shorts beside the banister. The lights are dim; it’s after bedtime for both the children—and adults. We are about to ascend the staircase to bed, bleary-eyed. We’re too tired to talk tonight, but this is our only time not to be heard (as far as we know) by the little ears of our oldest, a four-year-old with the memory of a muse.

“But I know that’s crazy, and I never want to be that sick again,” I hurry. The words rush out like a train whose cars are colliding into each other. The fantasy of no hyperemesis is dashed by the look on his face, and how it mirrors reality: Leo’s expression bears no trace of amnesia.

“We can adopt?” he says.

“True,” I say, instantly trying to shrug off the tens of thousands of dollars and miles of improbability that I know adoption entails by categorizing it on the shelf in my mind labeled “possibility.”

But then there’s my other question: “What if I die, or we divorce, and you want to have more children?”

He’s clear about that. He doesn’t want children with anyone else.

Then my final question: “Do you really want to do that to your body?”

This, he may sense, is a sort of test of his feminism—after all that has happened to my body, which I occasionally, in tears, refer to as “mutilated” despite my immense fortune of having had “easy” and “textbook” births (textbook births are still akin to being ripped in two). If it is a test of his feminism, it’s only semi-conscious on my part.

The window is cracked. The neighbor’s lilac tree breathes through. The adolescent leaves on the oaks and maples rush into the wind as a soft brush of wings. The goldfinches have been shedding dark feathers and reflecting their names in shimmering new light, and they chirp now happily.

“It just seems,” Leo says, “like the evolved thing to do.”

***

That night, I can’t sleep. Our baby is in the crib beside me. My brain, my heart, my lungs—all in flux. I sweat, but it’s cold. Ducts pulse and release, milk for her, hormones for me, energy in my body that rushes in and out of balance. I would never in a million years get pregnant now anyway, so soon after a baby, not even a year, I tell myself; so soon for me, someone, I think, so easily thrown off by change.

I begin to cry into my pillow, as though someone is dying, and Leo hears me and asks if I want to keep talking. “It just doesn’t seem fair,” I say, “that we can’t do this one thing, because I’d get so sick, but—”

“I know,” he whispers, and I cry as quietly as I can so I don’t wake the baby, and we sleep, and Frank grumbles beside us, and I feel very sad even in my dreams, but tomorrow, when the light shines into the window, I will know that there’s more to this decision than the hyperemesis; that there’s an impossible line I am trying to straddle, a question I can’t answer: What does it mean to love motherhood with your whole heart, while not wanting to be consumed by it?

***

The next day I get my period, a timing that seems too absurdly obvious to be true. It brings with it its usual relief and clarity. Revelations are most likely in the bathroom these days anyway, with kids playing loudly outside it (or in it), so it’s fitting that today is no different.

I know now that the past five years of two kids, of two debilitating pregnancies, and their recoveries have tumbled together and on top of me, making it hard not only to see ahead but behind.

Should it be a surprise that the very thing in me that could carry a baby—as though agreeing with me—is shedding its skin like a snake? As though to ask: Could you grow into a new kind of motherhood, and alongside it, into someone besides a mother, even someone you’ve known once before?

Marni Berger holds an MFA in writing from Columbia University and a BA in Human Ecology from College of the Atlantic. Marni’s short story “Hurricane” appeared in The Carolina Quarterly 2020 summer issue and her short story “Edge of the Road with Lydia Jones” was nominated for a Pushcart Prize (Matador Review). Her short story “Waterside” appeared in Issue 96 of Glimmer Train. She has been a finalist or received honorable mention in nine Glimmer Train contests and one New Millennium Writings contest. Marni’s novel-in-progress, Love Will Make You Invincible, is a dark comedy about a mother and her precocious tween. Marni lives in Portland, Maine. She has taught writing at Columbia University and Manhattanville College. She currently teaches writing at University of Southern Maine.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

You know it’s an amazing year to be a reader when Emily Rapp Black has another book coming. Frida Kahlo and My Left Leg is remarkable. In this book, Emily gives us a look into how Frida Kahlo influenced her own understanding of what it means to be creative and to be disabled. Like much of her writing, this book also gives us a look into moving on (or passed or through) each day when it feels like everything is gone.

Pick up a copy at Bookshop.org or Amazon and let us know what you think!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Are you ready to take your writing to the next level?

Two of our favorite writing resources are launching new opportunities for working on your craft. Circe Consulting was formed when Emily Rapp Black and Gina Frangello decided to collaborate on a writing space. Corporeal Writing is under the direction of Lidia Yuknavitch. Both believe in the importance of listening to the stories your body tells. If you sign up for a course, tell them The ManifestStation sent you!

Anti-racist resources, because silence is not an option

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~