I live in a leafy northern suburb of New York City, and I am blessed with trees and ponds, deer, chipmunks, and songbirds galore. There’s a big pond about a mile from my house. When my gym shut down in March of 2020, I resorted to walking as recreation, and I chose the pond as my almost-daily walk’s destination. Since I live in a warren of cul-de-sacs, there is no block to walk around, as in “take a walk around the block; you’ll feel better,” one of my late mother’s favorite bits of advice. So, at some point I have to simply stop, turn around, and head home.

The pond has become my turn around point.

It’s a big pond, maybe two or three acres big (I am terrible at estimating such things) and sits on town land, about ten feet back from the road. In good weather I sometimes stop for a bit and look around, feel the breeze in my hair, listen to the cardinals scolding, the woodpeckers and titmice chirping, the tree frogs chattering. There’s a bird that sounds like a rusty swing: seeee-saw, it whistles. I like to watch the surface of the water, looking for the wide mouth bass reputed to hide out in the shallows. Last summer a big bull frog would protest if I tossed a stone in the water, bellowing like a moose.

All through the first Covid year, I turned around at the pond, then the next. Now here I am again, two years later, spring 2022. I toss a pebble, and there is silence; the bullfrogs haven’t emerged yet from their muddy hibernation.

Yesterday, two Canada Geese greeted me at the near side of the pond. The pair waddled toward me a little, then stood silently, watching me pass by – I was aiming for the far end of the pond that day. I found myself wondering if they are the same pair who nested here last summer. Two Aprils ago I wrote in my journal,

Little pond looks still

then tall brown grasses rustle—

a goose making a nest.

All through that first COVID spring, summer and fall I watched them. First just the pair, with their sleek brown-feathered bodies and black velvet neck and head, the wide white stripe near their eyes. There were several days when I saw only one goose, and I hoped that meant the female was on the nest, back on the far side of the pond, where a stand of tall, dried marsh grasses and cattails stood. And then came the day when I saw the adults leading three fuzzy goslings for a swim. By late summer five look-alike geese lolled at the near side of the pond, munching on grass or snoozing in the dappled shade from a nearby oak. For a couple of weeks midsummer, they were joined by an egret, who kept to him- or herself at the opposite end of the pond, a white statue posing motionless on a fallen tree trunk, which I bet made a great spot for locating fish. In early October, I counted seven geese. I suspected that my goose family had been joined by two northern relatives stopping by on their way south for the winter.

And then all seven were gone—off to the Carolinas, I supposed.

And then my younger sister Grace died, just as suddenly, struck by a burst aneurism while eating dinner. A seemingly healthy, happy woman., she was gone in less than five minutes. The quiet pond over the next few months echoed my feeling of emptiness. For most of the winter it wasn’t even cold enough to freeze over. When it did, we had a few days of kids ice skating. But various logs and tall grass stalks interrupted the icy surface every here and there, making skating difficult. The kids gave up before the ice did.

***

As the days move through the seasons, warming up, then growing cold then warming once again, the pond has become somehow a reminder of Grace. It seems to not change at all for weeks at a time, then suddenly after an absence of a few days, everything seems different. It has frozen over; it has thawed. The geese arrive; a heron visits for a day or two. The leaves on the trees turn red and gold. And Grace is not here to see any of it.

And now, it’s spring again. I wonder if the geese at the pond this spring recognize me. But, of course, all Canada Geese look alike; it could be any two random birds there. I am struck that we humans are interchangeable like that.

I feel bad about my sister’s life being cut short. I already miss her, with her sincerity, her astute observations on people; her love of laughter. Her coaching clients will miss her wisdom. Her grandson will miss his Grandma Grace and her annual visit from California at Thanksgiving. Her daughter, given up for adoption when Grace was just a teenager and lost to us for so long, will miss her new-found birth mother. When the eligibility age for COVID shots was lowered last year, I thought for a moment, oh good, Grace qualifies now. And then I realized that she won’t get to see the end of this pandemic. Sometimes I wonder if any of us will.

Grace died in October of 2020, and already she’s starting to blur. I sometimes get little snatches of memory –me back in high school, yelling at her because she’d been into my lipstick and mascara (we shared a room and she was four years younger) – or the time we entered a contest to win tickets to see the Beatles at Shea Stadium by drawing the biggest Beatle Picture – pasting together reams and reams of newspapers and drawing a copy of the Beatles album cover with Magic Markers. I climbed out on the roof of our house to take a picture of her standing next to it spread out on the grass. (We didn’t win.) Or the way she looked sitting on my couch back in Buffalo, where I was in grad school. She was so young, seven months along, playing with the kittens someone had left on our doorstep in a big cardboard box. But now there’s no one to share those memories with.

Grace’s clients will find a new life coach. Her daughter will carry on as one of the elders now, someone with her own recipe for banana bread and her own methods to remove stains from carpets. Grace will fade to a distant, if cherished, memory. And I wonder, is there anything I have done in my life that will have made any sort of difference in this world? I’ll die or move on to an assisted living facility and a youngish couple will move into my house. They’ll change out the paint color in the living room and redo the kitchen. They’ll take their children for walks to the pond and try to catch the long-mythologized wide mouth bass. And it will be as if I never lived here. I’m just another Canada Goose, indistinguishable by my plumage, making a few last circuits of the pond before it ices over.

The days are getting longer. The forsythia have bloomed and cherry trees are showing off their pink and white blossoms. Still no sign of nest-making at my pond. The sun rises higher in the sky, and the water is still. I guess the geese have found a new home somewhere else. The rusty-swing, seee-saw-calling bird sings out from its hiding place, seee-saw, seee-saw. I turn and walk home.

Katherine Flannery Dering received an MFA in 2013 from Manhattanville College. Her memoir, Shot in the Head, a Sister’s Memoir a Brother’s Struggle (2014, Bridgeross) is a mixed-genre book of poetry, prose, photos and emails about caring for her schizophrenic brother. Her poetry chapbook is titled Aftermath (2018, Finishing Line Press.) Her work has appeared recently in Inkwell, RiverRiver, Cordella, Adanna, Goatsmilk, Share Journal, and Landing Zone Magazine, in addition to The Manifest Station. Her website is www.katherineflannerydering.com.

***

Wondering what to read next?

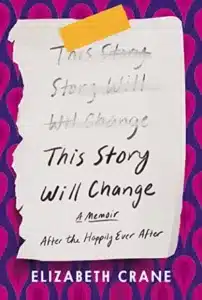

This is not your typical divorce memoir.

Elizabeth Crane’s marriage is ending after fifteen years. While the marriage wasn’t perfect, her husband’s announcement that it is over leaves her reeling, and this gem of a book is the result. Written with fierce grace, her book tells the story of the marriage, the beginning and the end, and gives the reader a glimpse into what comes next for Crane.

“Reading about another person’s pain should not be this enjoyable, but Crane’s writing, full of wit and charm, makes it so.”

—Kirkus (starred review)

***